The analog foil to digital enshittification

Rhea Purohit reads a lot and writes about what she discovers — both at the knife-edge of technology and buried in old businesses.

Are you reading this on your laptop, in a tab wedged between 23 others that you’ll likely forget to close? Or on your phone, where you’ve already swiped away two Slack pings?

Oh, and a third just appeared — plus an email from your VC has joined the queue.

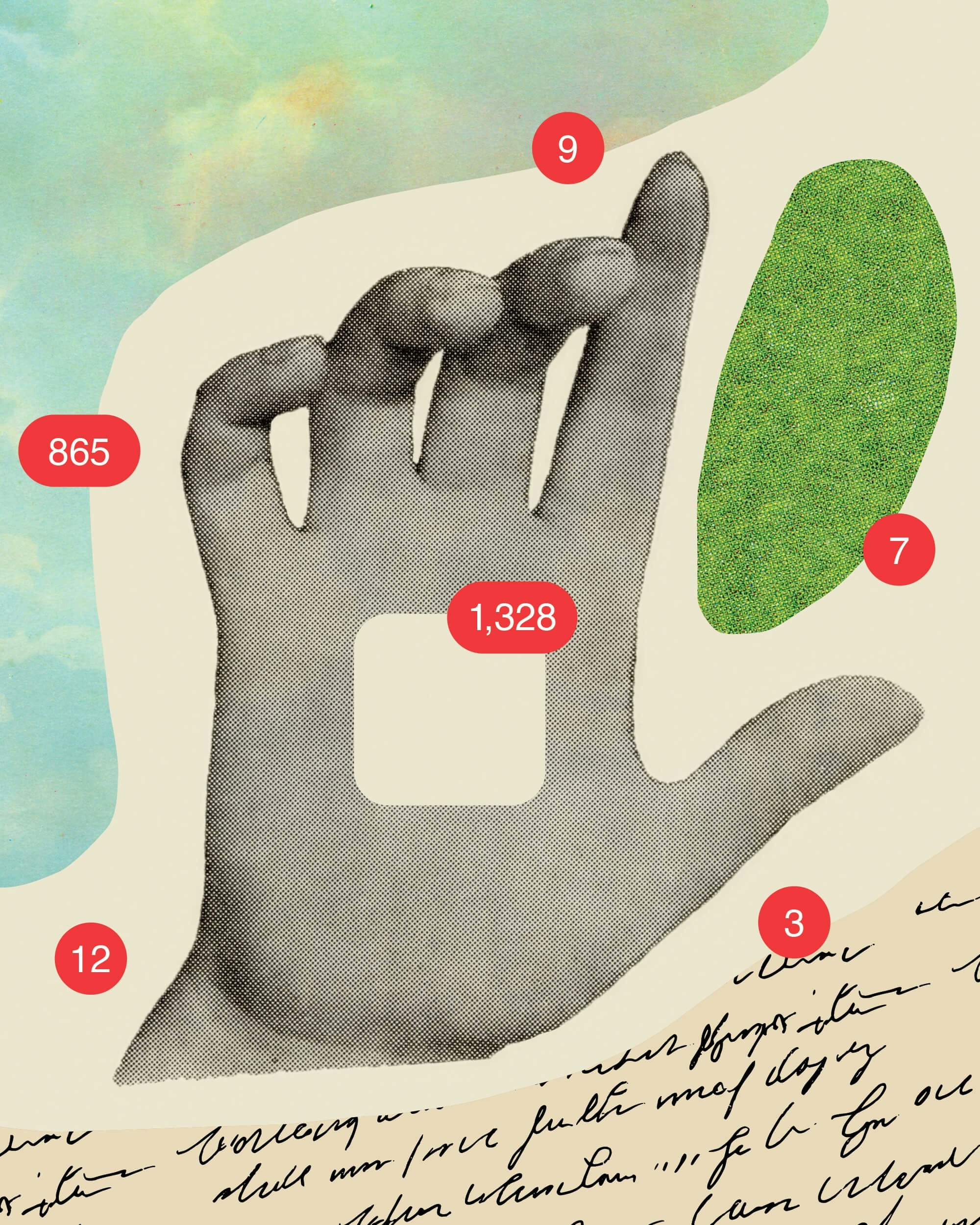

The pings, the badges, the little numbers… they’re always waiting.

That simmering pressure to respond comes from technology designed with purportedly good intentions: to help us save time, collaborate, find the right information, and so on. And while technology has, in many cases, delivered on that promise, as these tools seep deeper into the nooks and crannies of your work and life — glowing, clickable, always within reach — they’ve begun to spin a sticky web around us.

Inside that web, we exist in a near-permanent state of interruption. Notifications, so often in that delectable shade of cherry red, tug at our attention, seducing us away from focused work and into a maze of apps, each one full of things to keep track of. Every new tool promises to make us more effective, but together, they create a new kind of work: switching contexts, remembering where things live, and constantly reassembling our attention. All the while, our fingers drift, almost involuntarily, toward bottomless social media feeds designed to keep us all scrolling.

To compound matters further, these digital spaces we inhabit are objectively deteriorating over time. For example, court records show that in 2019, a Google executive suggested a strategy that made search worse, so users would have to run more queries and see more ads. (And indeed, many share the opinion that the quality of Google search results has eroded over time, talking about the results pages as being stuffed with “garbage” content and product review spam.)

“Enshittification” is the charming term coined by author Cory Doctorow to describe this phenomenon, where, as many platforms mature, their goal shifts from making the product better to extracting more value from the attention it already captures.

What we’re left with is an uneasy bargain. If you’re a founder, you likely depend on these tools to get things done, and they probably influence your state of mind. But because each one is engineered to pull you back in — not to let you go — they can leave you interrupted and distracted, your focus splintered.

Before getting into how to loosen their grip, it’s worth taking a closer look at the root of the problem.

Why staying plugged in is so exhausting

In the pithy words of sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson, “The real problem of humanity is the following: we have paleolithic emotions; medieval institutions; and god-like technology.” Ronald Giphart and Mark van Vugt, authors of the book Mismatch, offer a startling way to grasp this: If you view human evolution as being an hour long, the first 59 minutes and 43 seconds would have us wandering the grasslands, hunting wild animals, gathering fruits, nuts, and honey. Agriculture and everything that followed — empires, the printing press, industry — fill most of the remaining 17 seconds. The digital revolution only arrives in the final 0.03 seconds, and has already staked a claim on the majority of our waking hours, all in pursuit of generating revenue.

Humans are wired to make decisions based on what we can see, hear, smell, and touch — but for knowledge workers especially, modern life demands that we spend our days inside intangible digital spaces. A theory known as “evolutionary mismatch” suggests that when our environment deviates sharply from the one we evolved for, the gap between the two becomes a source of cognitive stress.

And as the time we spend using digital interfaces increases, with many of them quietly decaying of their own accord, this gap yawns wider — making it harder than ever to create conditions which nurture deep work and focused thinking.

Learning to use technology (without being used by it)

To be clear, the solution is probably not retreating into the Stone Age (and yes, this article was both written and is being read on glowing screens of variable sizes). There’s no doubt that digital technology is useful — but because of how we, its fallible creators, have evolved, we may well be especially sensitive to some of its darker effects.

There is a way to reap the benefits of these tools without letting their worst dynamics set the rhythm of your day. The foil to technology’s shapeless pull, it turns out, is something you can actually touch: the physical, tactile, analog. Developing practices grounded in the analog — like writing on paper, (literally) touching grass, or knitting — offers cognitive benefits that you can carry back into how you use digital interfaces; a recalibration of sorts.

Now, even if you’ve been nodding along so far, you might balk at the idea of ceding any of your screen time. When you’re chasing a goal close to your heart, even the smallest step away from technology can feel like giving up leverage. So let’s make this practical: below are some of the worries founders have about making room for the physical world alongside their screens — and suggestions for how you can, with the right balance, earn that leverage back in spades.

#1 “I’d love to go offline — even for a quick half hour break — but I can’t help but refresh my inbox every now and again. What if I miss something important?”

First, let’s address that fear directly. How often has something truly catastrophic happened because you failed to respond immediately? For most of us, the honest answer is rarely, if ever. Most “urgent” messages can wait, at least a little while — and the few that genuinely can’t will usually find you through other channels: a knock on the door or a colleague walking over to your desk.

It helps to build systems that let you step away with confidence. Create a simple triage: What truly requires an immediate reply? What can wait an hour? What can wait until tomorrow? You’ll likely find that the “immediate” category is far smaller than your anxiety suggests. And for those rare genuine emergencies, designate a backup channel — like a phone number, a specific Slack channel — so you can mute the rest without worry.

With that safety net in place, you can go reap the benefits of your break. Because on the whole, staying available all the time is corrosive to your attention — and choosing strategic moments to step away can give you an edge.

#2 “Working with my hands — by writing with a pen and paper — is a great idea, but I handle a lot of data and need easy ways to share what I work on with others.”

Many work products — like a sprawling spreadsheet that needs sign-off from three teams — are almost certainly best served by digital tools. But the whole process, from ideation to execution, doesn’t have to happen online. There are real cognitive benefits to moving some of your thinking onto paper, even if the final deliverable lives on a screen.

Writing by hand offers something typing can’t. When you type, a near-identical finger movement — tapping the bevel-edged keys on your keyboard — creates every letter in the alphabet. Writing by hand requires a different movement for each letter — forming a “J” is different from an “M” is different than a “Z” and so on — and it engages your motor system in a way that binds action to memory. Brain scans show handwriting activates a wide network of regions responsible for movement, vision, and sensory processing, and in turn deepens your conceptual grip on whatever you're working through.

Try reaching for pen and paper in the early stages of a project: sketching how data should be structured, roughing out a prototype, thinking through a problem before the Google Doc is even open. Nvidia’s version of this is a marker and a whiteboard. The company’s conference rooms are lined with whiteboards because CEO Jensen Huang believes they force rigorous, transparent thinking — a way of laying out ideas as clearly as possible before they're committed to code or slides.

An interesting product that sits at the intersection of the digital and the analog is Moleskine’s line of “Smart” products: write in their elegant notebooks, and your notes sync to a companion app (a charming echo of Moleskine’s former partnership with note-taking software Evernote).

#3 “I’m already exhausted by the end of the day and don’t have the time or energy to do more things.”

While the drained feeling that washes over you when you push down your laptop screen is real, it’s worth thinking more about where it comes from. The exhaustion of a day spent on screens is different from the sweaty soreness of a long hike. Digital fatigue is a type of overstimulation because you’ve been processing fragmented inputs and switching contexts for hours. And if screens follow you into the evening, they chip away at your sleep too, disrupting the circadian rhythms that help you recover.

Doing something with your hands, even when you’re feeling that cognitive drain, can be surprisingly restorative because it taps into a different part of your brain. “When you look at the brain’s real estate — how it’s divided up, and where its resources are invested — a huge portion of it is devoted to movement, and especially to voluntary movement of the hands,” said Dr. Kelly Lambert, a professor at the University of Richmond in Virginia, in an interview with The New York Times. Typing and mouse-clicking technically count as hand movements, but they’re narrow and repetitive — the same small motions, over and over. Instead, think: kneading dough, sketching, or even just doing something small around the house.

It’s telling that even the companies building the future of AI are leaning toward drawing people away from their screens and out into the real world: for example, Anthropic’s viral “Thinking Cap” campaign involved setting up at cafes and handing out branded merch, banana bread, and coffee.

The ambition of your analog pursuit could range from cooking a nice meal to just walking somewhere (even if it’s already dusk) without looking at your phone. You’ll return to your desk the next day sharper for it.

Stack the deck in your favor

There’s a small but growing set of products intentionally designed to protect your attention. The Daylight Computer Co. does this through strategic constraints — the device’s screen, as CEO Anjan Katta described to Meridian, is “freaking black and white without crazy high contrast.” That limitation makes scroll-hungry visual apps like Instagram and TikTok feel dull, while reading apps become the natural default: “more Kindle, Google Docs, PDFs, Substack.” On the software side, Cosmos takes a similar approach — a creative tool designed to help you discover and organize ideas, now evolving into a social platform built around aesthetics rather than the addictive loops that dominate most feeds.

Beyond seeking out products like these, you can change the way you meet digital tools by building a robust parallel life beyond the screen — analog practices that leave you feeling more intentional with how you spend your time and attention. The analog is where attention repairs itself, so you can return to your digital work sharp, steady, and in control of what you give your mind to.

About the author

Rhea Purohit reads a lot and writes about what she discovers — both at the knife-edge of technology and buried in old businesses. She’s written for Every and Asimov Press, and is building a library of business case studies for Cedric Chin at Commoncog. She’s writing to you from Valencia, Spain.

Related reads

Reframing creativity: How I quit my job (but not really) in order to be better at it

Dreaming in daylight