Reframing creativity: How I quit my job (but not really) in order to be better at it

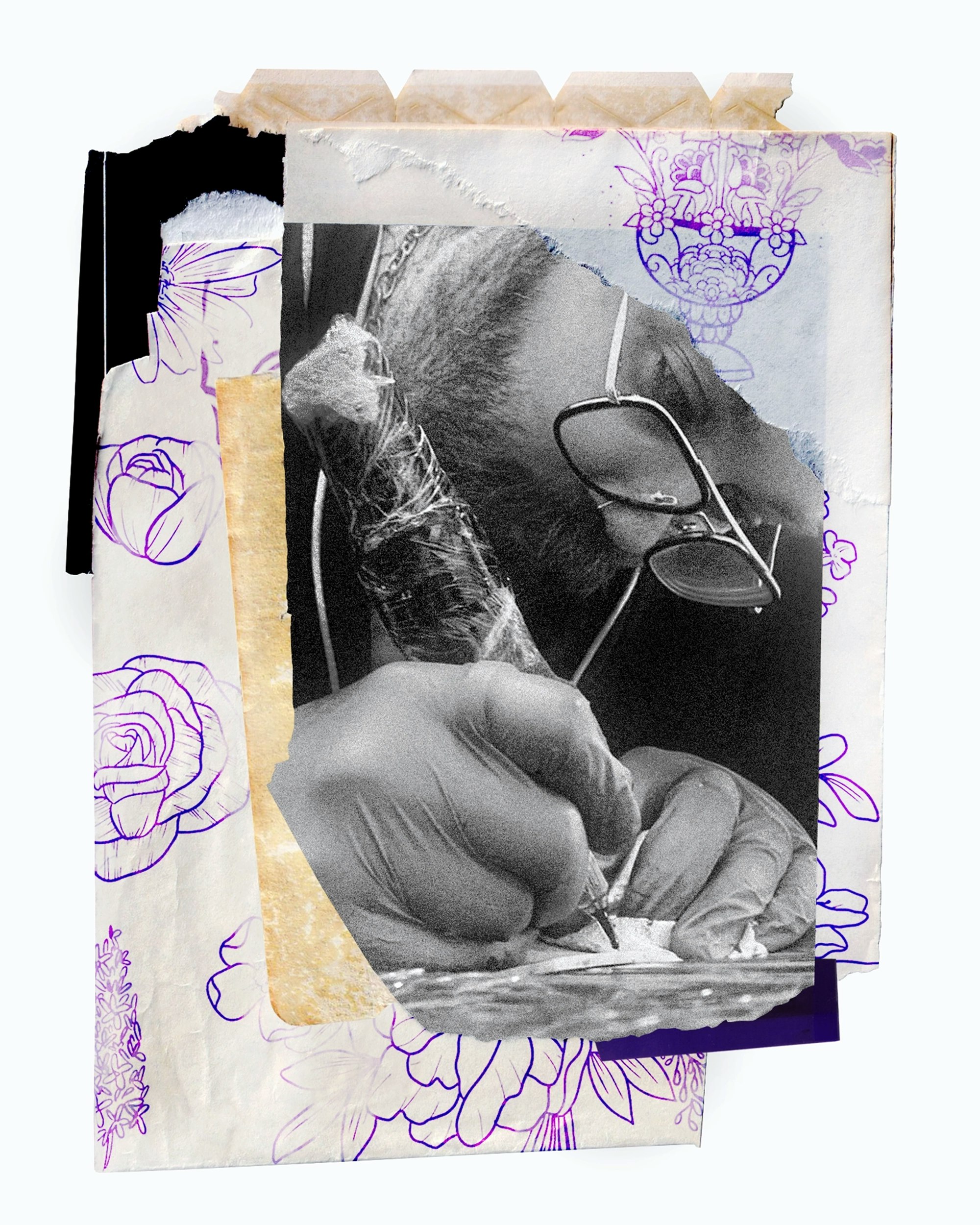

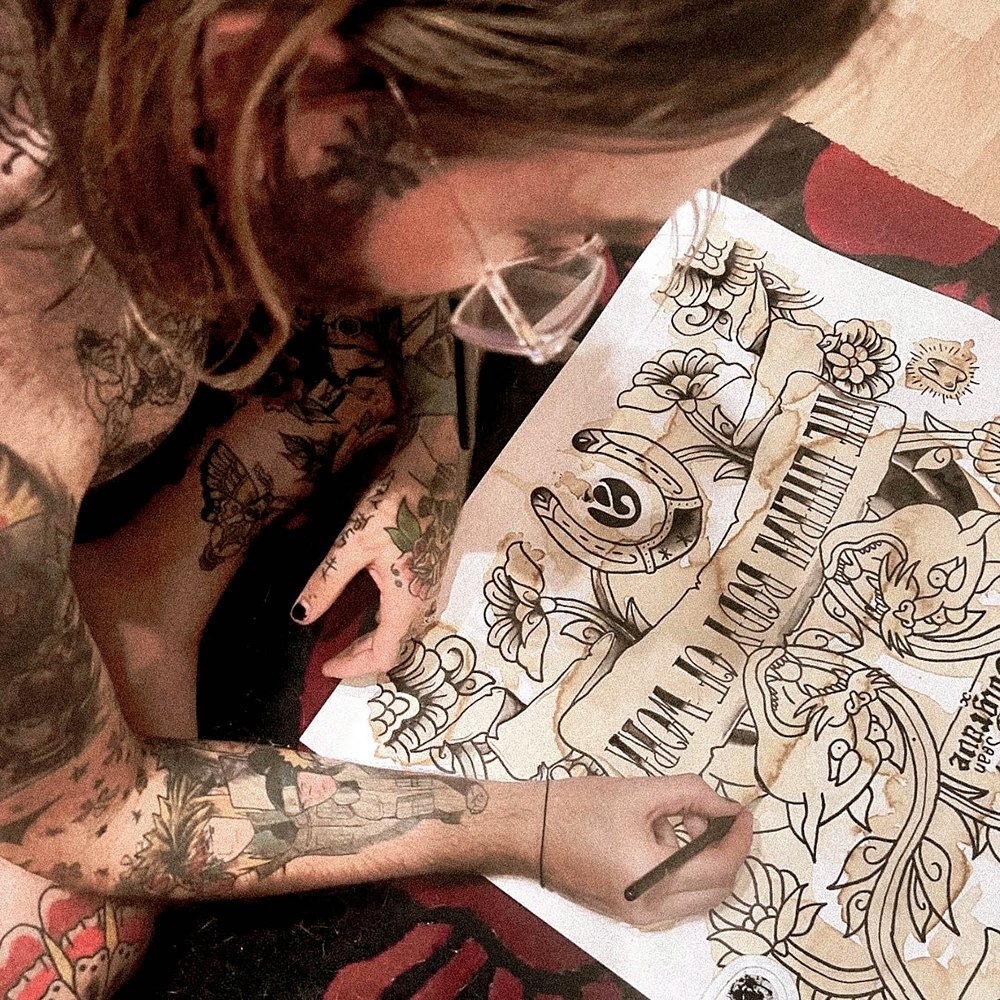

Sean Colgrave is a tattoo artist and arts advocate based out of Nottingham in the UK.

I didn’t set out to become a tattoo artist, but I always knew that I wanted my career to be creative. I remember sitting in school and talking about what I wanted to be when I grew up — like many children my age I wanted to be an archeologist because I thought they carried whips and raided temples. But when those talks really mattered? I sat telling my career counsellor, “I want to work in game design, like concept art and art direction” only to be told that work didn’t exist.

I tried to take every creative lesson I could in school, aiming to do a graphic design course alongside one in art, only for my mother to ask, “Do you really need to do drawing twice?” Like many, I grew up with the pressure to pursue work that provided stability: “something reliable,” “something that pays,” “something you can explain to your parents’ friends.”

So, at first, I followed a more traditional path. I went to university and put my creative ambitions behind me, choosing to study geography and philosophy. The former was a practical and academic choice ( I was good at it and thought it would lead to a good job), but the latter was for me. It felt like another path for a creative outlet.

When I left university, I tried to go into teaching, but that didn’t go as well as I’d planned. I bounced around a few jobs before working my way up the ladder at a call centre until I was firmly in middle management. I worked hard. I was capable and competent. But I was also deeply disconnected from myself.

Then my son was born, and that changed everything.

Becoming a parent made me confront the life I was modeling for my kid. Was I really going to teach him that passion is optional? That money matters more than meaning? That being true to yourself was a luxury, not a necessity?

I couldn’t do that. Some part of that desire was a selfish quest to reclaim myself, because how could he be proud of me if I wasn’t proud of myself? I needed him to see that creative people deserve space. That making things can be a livelihood. That art isn’t just something you hang on a wall, it’s something you live through.

Becoming a parent made me confront the life I was modeling for my kid. Was I really going to teach him that passion is optional?

Then I found tattooing. Not as an art form (I was already pretty tattooed at this point) but as a path. An old friend of mine from school had been tattooing for over a decade, and I confided in him that I wished I’d known he was leaving school to pursue tattooing — and I wish I could've gone with him.

“Why don’t you just do it?” he asked. Having that encouragement, and a friend in my corner, was like a lifeline, and a way back to creativity. I’d seen every episode of Miami Ink at this point, and my head spun with a possible future. I’d heard of the starving artist, but never the starving tattooist.

Tattooing was good to me. I felt more grounded in my work than I ever had in any office. I built a small practice and a community. I wasn’t the best out there, but I carved my own little space somewhere in the middle of the pack. People trusted me with their stories, literally carrying them on their skin.

And as I tattooed more, I realized what I was doing wasn’t just about decoration. It was about transformation. Reclamation. Identity. A realization that would become a lot more important later on in this story.

For a while, tattooing was enough, but the warnings of my youth came home to roost: passion doesn’t always pay the bills, especially not in a turbulent economy. A few years into tattooing at others’ shops, I moved on to start my own place, but then COVID hit. I had to close the doors for 18 months. (How could I tattoo someone from 2 metres away?)

When I finally found myself back in my shop, the initial few months were incredibly lucrative. After being cooped up for so long, lots of people wanted to mark their sentence with ink. But that soon dried up.

Many other “tattooers” had newly sprung up with Amazon-bought machines, tattooing out of their houses for a pittance. Suddenly, I was working every hour just to keep the lights on, dropping my prices or compromising my vision in order to compete with my environment. It was a race to the bottom that only got worse with subsequent financial tumult in the UK. I found myself facing a question that creative people know all too well: Is this sustainable? Is the mounting debt worth my happiness?

I found myself facing a question that creative people know all too well: Is this sustainable? Is the mounting debt worth my happiness?

I didn’t want to quit, and I couldn’t go back to the office. The genie of creative ambition had been let out of the bottle, and there was no way of getting it back in. But I did need to step back and reassess. I needed to figure out what “creative success” meant for me now. I was barely treading water with my finances, working 60, 70, 80 hours a week. I was working so much that I was no longer seeing my son, and all my personal relationships were suffering. If I stopped treading water, I feared I’d drown — but my legs were getting really tired.

Instead of playing it “safe” and returning to the corporate world, I made a leap that surprised even me: I joined an experimental Master’s program that promised to help creatives develop more sustainable practices. I thought it would be about sharpening my art skills. Instead, it asked bigger questions about value, visibility, and infrastructure. About how creative work actually reaches people. About how to build systems that support art, not just extract from it.

Unlearning; learning

I was part of the program’s first cohort. We were all figuring it out as we went — students, faculty, the program itself. That messiness was uncomfortable at times, but it mirrored the creative process. It, like tattooing, felt honest.

And it reshaped how I think about my work. Not just tattooing, but the broader story I’m telling as an artist, a parent, a collaborator, and a human. Before the course, I judged my work from the inside out. If a tattoo didn’t turn out quite how I’d hoped, or a client didn’t rebook, I took it personally. I’d spiral. The story in my head was: You’re not good enough.

That mindset — maybe more than any measurable or economic factor — was not sustainable. In order to dismantle it, I had to find the distinction between myself and my work. I had to learn: You are not your work.

It sounds simple, but it’s powerful. Your work is something you make or do. It matters, but it isn’t the whole of you. And how others respond to it, whether they love it, misunderstand it, or ignore it, often has more to do with them than with you.

Here’s a truth that cracked something open for me: most people aren’t paying nearly as much attention to you as you think. You can remember your embarrassing moments from decades ago, but can you tell me the last time you noticed someone trip while walking down the street? The sense of constant scrutiny many of us feel is (mostly) imagined. We’re all in our own heads, worrying about our own failures and fumbles, much more than anyone else is.

That realization gave me room to breathe. To experiment. To try and fail and try again without attaching every outcome to my sense of self-worth. Reframing failure this way didn’t make failure stops hurting — but it allowed me to keep moving.

Who gets it?

Early in my program, we were asked a deceptively simple question: Who’s your audience?

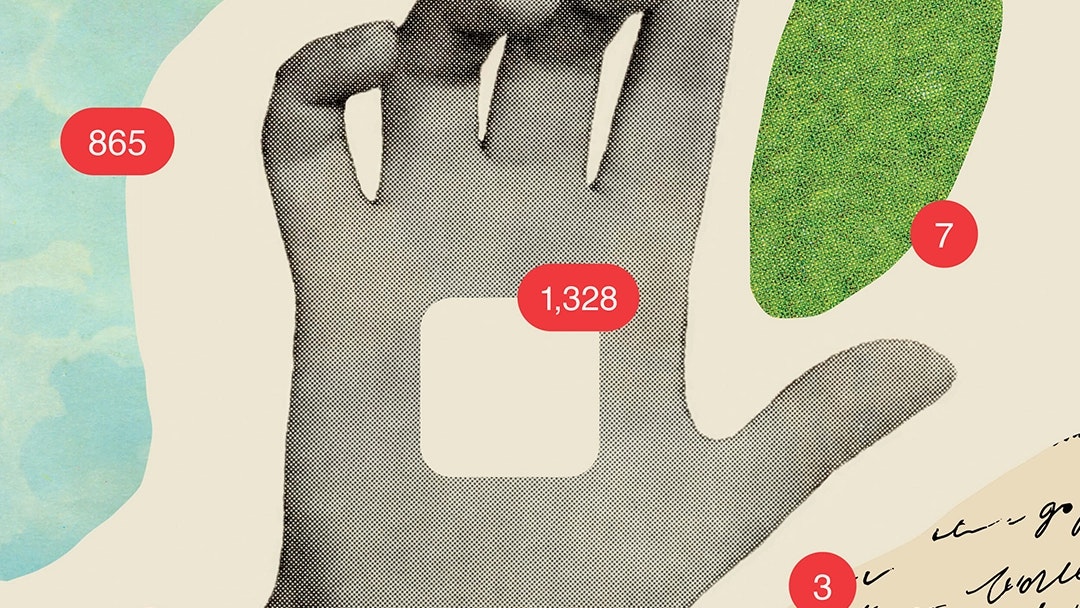

I bristled. The word “audience” made me think of algorithms and marketing decks — the commodification of people. I wanted to believe that art could just exist. That if it was good, people would find it.

But the more I sat with it, the more I realized that ignoring your audience doesn’t make you a purist, or put you in some mystical space that makes your art beyond reproach. It makes you less effective. Art is a story. Sometimes that story is really grandiose, and sometimes it’s just that you really like the color blue. But without an audience? Even the best story is nothing.

Your work is something you make or do. It matters, but it isn’t the whole of you. And how others respond to it... often has more to do with them than with you.

I realized that your audience is not “the general public.” It’s not “whoever shows up,” or uses the thing, or wants the thing, or buys the thing. Your audience is made up of real people, with real lives and real reasons for connecting — or not connecting — with what you make.

I started paying closer attention to the people I was tattooing to better understand my audience on a more specific level, and I soon saw the patterns. My clients weren’t just “people who like tattoos.” Many were older women who’d waited decades to mark their bodies. Or young queer folks claiming space in a world that tried to shrink them. Or people like me, tired of being asked to choose between survival and expression.

Tattooing offered permission. I was helping people say, “I belong to myself.”

And once I understood that, I stopped trying to appeal to everyone. I started speaking more clearly and more directly to the people who got it. And that clarity opened doors: invitations to speak, to exhibit, to write. My work started showing up in places I hadn’t even thought to look.

I learned that when you know who you’re speaking to, you don’t have to shout. You just have to speak with enough clarity and intention to be heard by those who want to listen.

Making peace

All of the above helped me ultimately change my relationship with rejection. Before I found the space between myself and my work — before I understood who I was really trying to talk to — every “no” felt like a judgment, or that feeling of not being good enough. Every unanswered email felt like confirmation that I didn’t belong.

But once I reframed all that, I recognized that “no” is just information. It helps you refine. Clarify. Adjust. It means something didn’t align — maybe the timing, or the pitch, or the person you reached out to wasn’t your audience after all.

I recognized, too, that rejection can even be a gift. It forces you to ask better questions. It nudges you toward something that fits better. It keeps you from wasting time trying to please people who were never meant (or inclined) to receive your work in the first place.

Creative ecosystems

For a long time, I thought being a serious artist meant doing it all myself. I wore every hat: artist, admin, marketer, accountant. And I burned out. Don’t get me wrong, the economic climate didn’t help, but I also had to take accountability for my own actions in spreading myself too thin while trying to “be my own boss.” But one of the biggest lessons I’ve learned is that collaboration isn’t a failure of independence. It’s a creative skill in itself. The beauty of creative ecosystems is that we don’t all have to be everything. We just have to be in conversation.

For a long time, I thought being a serious artist meant doing it all myself. I wore every hat: artist, admin, marketer, accountant. And I burned out. Don’t get me wrong, the economic climate didn’t help, but I also had to take accountability for my own actions in spreading myself too thin while trying to “be my own boss.” But one of the biggest lessons I’ve learned is that collaboration isn’t a failure of independence. It’s a creative skill in itself. The beauty of creative ecosystems is that we don’t all have to be everything. We just have to be in conversation.

Maybe it was a unique position from being on that maiden voyage during my later education, but I was surrounded by such a varied pool of creatives there — writers, filmmakers, singer-songwriters, photographers, illustrators, curators, designers. I partnered with people who would fill in my gaps. I stopped drowning in tasks I wasn’t good at. I started focusing on the parts that lit me up.

And in return, I could offer something others needed, too. Often that was money, but not always; some of my most valuable collaborations began as informal exchanges, rooted in trust and mutual curiosity.

One of the most surprising moments in this journey came when I was invited to curate an exhibition right in Mansfield, just outside the metropolitan hub that is Nottingham in the UK. I called it Miners, Misconceptions and His Majesty. It explored how tattoos intersect with class, identity, and belonging. (The exhibition is no longer listed on the museum’s site, but you can still find images and details on my Instagram and on the Mansfield District Council’s official website.)

Off-center, but in focus

Before the big Mansfield show, I tested a smaller prototype exhibition in London, showcasing my work alongside 15 other artists. I assumed the art would speak for itself, and that tattooed folks would turn up. I was wrong. Instead, I found myself chatting with local school teachers who wanted me to come and run a tailored class, a high-end designer looking for “something new” for their clients, and even a couple of retired bankers who were curious — asking how to interpret the pieces, how they were made, and what they meant.

That experience shaped the final Mansfield exhibition. I took myself out of the center and focused on the stories behind the work — the voices, the lives, the experiences. Even though I’m a tattoo artist, in this context I was a storyteller. The person connecting the dots, helping others to see tattooing as culture. I wasn’t saying, “Look at me.” I was saying, “Look at this.” And in doing so, people found me.

At first, I thought I’d just been lucky. But over the year it took to bring the exhibition from idea to reality, I realized this too was talking to my audience, albeit sometimes shakily and with a few stumbles as I learned how to find my voice in a new space. I was telling the right story, to the right people, just in a new way.

One audience member I met at the exhibition told me she’d always wanted a tattoo but couldn’t get one when she was younger. She wasn’t hanging around tattoo studios, but she was visiting museums — and that’s when it clicked that my audience didn’t have to be in the most obvious place for me. I just had to meet them in places where they already felt comfortable.

Let me be clear: I didn’t walk away from tattooing. I didn’t become someone entirely new. I didn’t burn it all down and start over. What I changed was how I saw the work, he questions I asked, and the way I moved through rejection, connection, and uncertainty. I found my reframes — it wasn’t reinvention, just redirection. I gained confidence that I could model a sustainable creative practice for son.

So if you’re feeling stuck, burned out, overlooked, or unsure, it might just mean you need to shift the lens. Step back. Zoom out. Find new language for what you’re already doing. Your creative path and the way you pursue your ambitions doesn’t have to be linear. It just has to be sustainable.

Three reframes that helped me

- Instead of: “No one’s buying my work.”

Try: “Who is this for, and am I actually reaching them?” - Instead of: “I’m not good at business.”

Try: “Who can I learn from or work with who is?” - Instead of: “I failed.”

Try: “What did I learn and how can I use it next time?”

Your creative life is more than a hustle. It’s a practice. A relationship. A way of being in the world. Sometimes you’ll need to pause. Not to quit, but to listen. Sometimes, stepping back is the most powerful step forward. You don’t need to choose between passion and practicality. You don’t need to start from scratch.

But you do need to own your story and tell it in a way the world can hear.

About the author

Sean Colgrave is a Nottingham-based artist, tattoo enthusiast, and journalist with a Master’s in Fine Arts and current PhD research into tattooing and identity. Passionate about elevating tattoos as a legitimate art form, his exhibition “Miners, Misconceptions and His Majesty” at Mansfield Museum examined their cultural significance within British society.

Related reads

A map of ambition: San Francisco

What embracing everyday magic can teach us about design

The analog foil to digital enshittification