Dreaming in daylight

Jonathan is a software designer and writer based in Portland, Oregon.

Morning expansion

Anjan Katta begins his day by letting it come to him. Instead of a buzzing alarm clock hastening his awakening, he’s greeted by warm, Kirtan music to gradually bring him out of bed. That warmth continues with a mug of hot water — not coffee or any other caffeinated beverage. He then sits on a ledge on his apartment rooftop, taking the time to absorb sunlight through his eyes and skin — readying his body and mind to greet the new day.

“I look for routines that draw me in, rather than pushing me awake,” says Katta. “It sets a tone of expansion rather than contraction.”

These quiet acts of expansion are microcosms of Katta’s approach to his personal life, daily rituals, and the chaotic rhythms of his role as CEO of Daylight Computer Co. The company is seeking “to build a more human computer” — one that offers the power of a digital experience with the natural feel of an analog one — all in support of the human nervous system. It’s a mission that requires an open-minded outlook to expand into new schools of thought, instead of retreating to well-worn playbooks.

Katta seeks to forge this path through experimentation, iteration, and deep thinking that builds off of their successful 2024 launch.

Read more stories like this one in Meridian: Details — on the subtle choices that shape how ambition comes to life.

The problems with modern computing

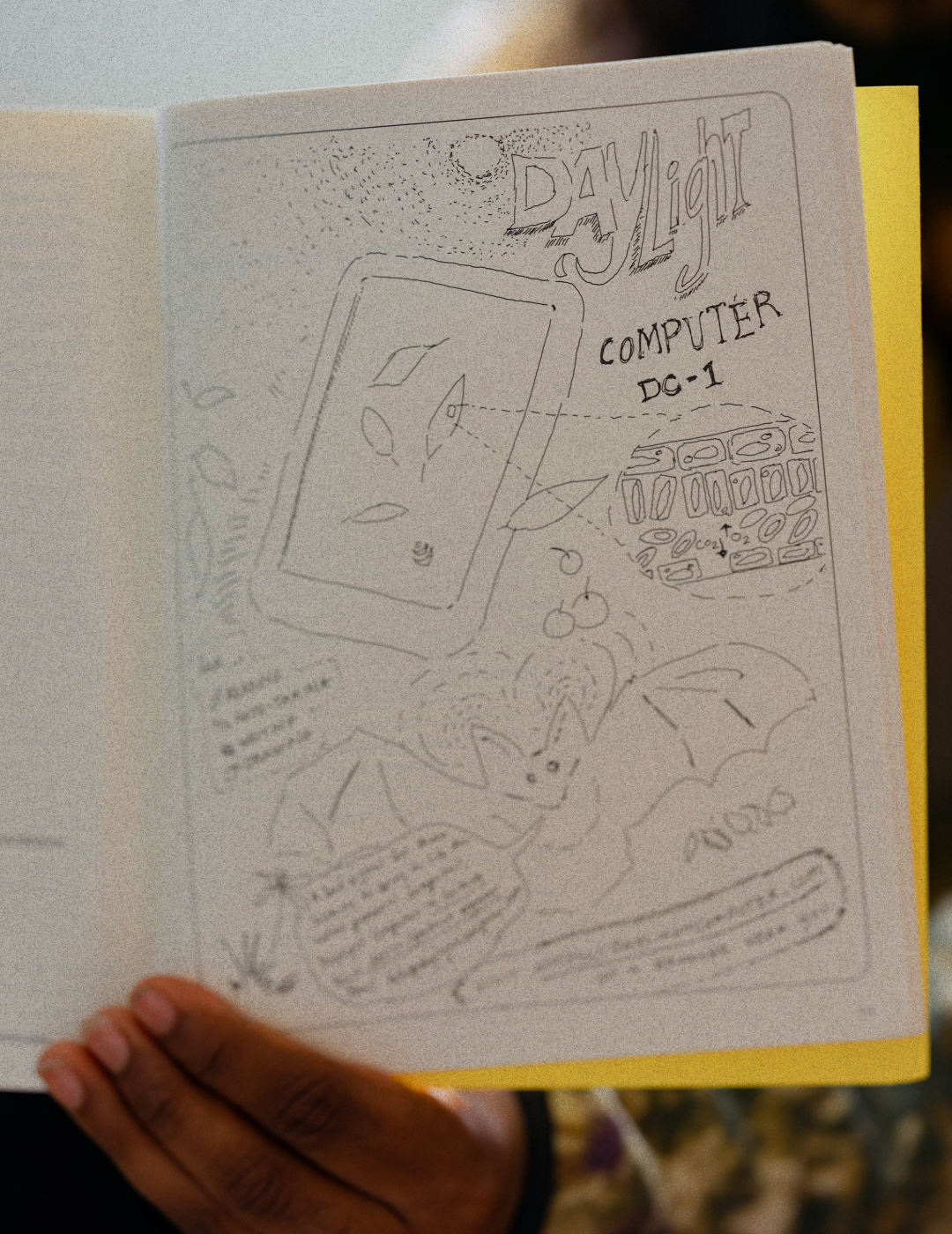

Katta affectionately describes Daylight’s first device, the DC-1 tablet, as “Maslow’s computer.” He perks up as he references psychologist Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs from 1943 — a pyramid illustrating how humans progress from basic, physiological needs (e.g., food, shelter, and safety) to more advanced ones (e.g., connection, intimacy, and respect from others) to the very top level of achieving one’s full potential and level of fulfillment, famously coined as “self-actualization.”

We’re not actually building computers... the real product is set and setting — environments that enable you to be the best version of yourself.

But Katta argues that modern computing has inverted this hierarchy entirely. Rather than helping people reach their potential through creativity and personal growth, today’s devices have become obstacles to the “good life” people seek. Instead of serving as a “bicycle for the mind,” as Steve Jobs envisioned, modern computing often falls woefully short by instead offering overstimulation and habits that are addictive — but not additive in any meaningful way. The culprits here are obvious: social media, games, and unintuitive, rote tasks that we often aimlessly perform on our various devices.

These computing habits disrupt human circadian rhythms — Katta describes them as “malnourishing” interactions. “It’s very hard to eat healthy when you have candy and onion rings right in front of you.”

“These spaces and headspaces of what a good life is — what allows me to be good, express good, do better… I keep sabotaging it with technology. It’s just really easy for [the technology] to end up in the configuration where it sabotages versus supports.”

Pursuing a healthier computing experience

Katta wants to resist the sabotage. “Daylight is an environmental design company, not a product design company,” he says. “We’re not actually building computers... the real product is set and setting — environments that enable you to be the best version of yourself.”

In pursuit of an environment that better serves humans, Katta arrived at the core insight fueling Daylight’s approach: “Computing is so much broader than just being defined by a glowing rectangle. Computing is the animation of something with interactivity and intelligence.”

To put this into practice: Rather than accepting the standard model of bright and alluring, Katta envisions devices that are more subdued, natural, and helpful. He references a Yoto Player: a screen-free audio player used by children, which operates by sticking a card in its slot and letting it tell you a story. Or a thoughtfully designed static object in your home that can suddenly come to life to become a Pomodoro timer that keeps you on task. Or a painting on your wall that is generated computationally. These whimsical, yet practical references help illustrate the kinds of interactions that Katta hopes for computing — delivering environments and experiences that nourish users and support them at each level of Maslow’s Hierarchy.

The challenge lies in balancing idealistic vision with practical utility — building machines for real people in real-world scenarios. For the DC-1, this means a tablet that may not initially look like the shiniest, most enticing gadget to use — but aims to deliver a natural experience for its user.

The magic of constraints

Daylight’s design ethos might surprise founders accustomed to elaborate processes and first-principles thinking. His team’s R&D methodology is refreshingly empirical: “Buy it. Try it. Feel it.”

The team’s hands-on experimentation includes buying old CRT monitors on eBay, testing different aspect ratios, and visiting computer history museums to try vintage technology. “It’s a lot less glamorous than fancy 3D printing an awesome design or having intense brainstorms,” Katta says. But this approach is how Daylight uncovered key insights around display and LED technology that have been largely ignored by other companies.

Nothing has shifted in Katta’s core thesis since launching the DC-1, an e-paper tablet that’s faster and more fluid than traditional e-ink displays, and eschews the blue light of standard screens. The device represents years of work to solve what Katta sees as fundamental problems with how we interact with technology.

The matte, off-white plastic housing and amber LED backlighting of the DC-1 embodies what Anjan calls his “Harry Potter vision of computing”: technology that feels magical because it’s “tactile, kinesthetic, and textured,” rather than sterile and futuristic.

Importantly, the constraints of the hardware are an essential part in Daylight’s mission to build devices that respect human physiology. “Light is a high-bandwidth interface for the human nervous system,” Katta explains. By eliminating blue light and the 500-times-per-second flicker of standard LED screens, the DC-1 aims to transform computing by making the apps and services we all use much less taxing.

“It’s freaking black and white without crazy high contrast,” he says.

Instead of fighting addictive apps through software restrictions (and thus not imposing any paternalistic censorship), Daylight instead intentionally creates environments that don’t cater to those apps — ones in which aimless scrolling naturally becomes less engaging. “Instagram sort of sucks on Daylight. TikTok sucks on Daylight. We don’t need to tell people how to use this. Just by the constraints of the hardware, I’m reading more — more Kindle, Google Docs, PDFs, Substack,” Katta says. “Technology becomes so powerful when you can start to resolve some of the psychological dynamics.”

The power Katta alludes to is not just perceptual. The advances in paper technology that he unearthed over multiple research trips to Japan enabled Daylight to build the first device of its kind, a tablet with all the benefits of e-paper that has an incredible 60–120Hz refresh rate — something no other device in its class has achieved. The end result is a device with digital capabilities, but with the smoothest reading experience you can find short of turning the page of a book.

Navigating the “second album”

In spite of these breakthroughs, the pressure on startups to demonstrate their market fit and growth prospects remains. But Katta has a fresh approach that’s also in tune with Daylight Computer’s future growth prospects — and the company culture he’s building. Unlike many Silicon Valley startups that measure success through unit sales or monthly active users, Daylight’s organizational North Star centers on something more elusive — preserving taste, instinct, and creative quality over time. In many ways, he’s seeking self-actualization not only for the users of his products, but for his very team.

“Our internal definition of success is: are we keeping our cups full... so we can keep doing the next 10%?” he says.

Focus on doing your best work. The market will exist for you and others — it’s not always a zero-sum game.

DC-1’s success has created what Katta calls “the second album problem” — how to maintain creative vision while managing the pressures of a growing business.

“An artist’s first album is awesome because they’ve been working on it with no side distraction for like five years. For the second album they have to write music while being popular and touring,” he reflects. “The second album is harder. You have to create while being watched.”

Post-launch, Daylight has faced pressure to optimize for conventional growth metrics and navigate user expectations, which are varied. “I tend to not orient my definition of success around output variables. I don’t really get to control how many sales we have; I get to control how many people I talk to or what features we ship.”

Katta describes how everyone he talks to is enthusiastic about their particular vision for how the “more human computer” philosophy should manifest. Some tend toward the pole of complete restriction: “ban social media... you literally cannot even go on [X]/Twitter.” Others tend toward seamless integration: when they save a tweet to read later they want to be able to open it in the browser. Either end of the spectrum (total restriction versus allow everything) sees their approach representing the clear way forward. The right balance for Katta lies somewhere in between.

His approach to this challenge reveals sophisticated thinking about sustainable growth. “The goal isn’t to chase growth metrics but to create thoughtful, beautiful products that resonate deeply over time.”

Katta’s core beliefs extend to the way his team operates. Daylight prioritizes the team’s capacity for deep thinking and empirical experimentation. Part of this is protecting the team’s schedule. Another part is preserving the environment that led to innovation in the first place. “I think often people [visit our office and] say, gosh it’s all very fluffy and textured and cozy,” he notes. The office features fuzzy carpets, soft lighting, and “stuff that feels good for your nervous system.” It’s designed according to the same principles as their products — thoughtful, considered, human.

This extends to his rhythms as a CEO. While the demands of Katta are not dissimilar from many CEOs, he insists on creating pockets of time in his schedule to protect what he describes as “liminal thinking time.” Space for his mind to wander and explore tangents that intersect with problems the team is trying to solve. Through all the chaos, Katta prioritizes his time to mull Daylight’s most important questions, even if that means not addressing every detail or attending every meeting.

The philosophy has practical implications for how Daylight approaches partnerships, hiring, and product roadmap decisions. “We were so hard to fund, and so many of the institutions and conventional people all said ‘no.’” Katta reflects. “The hard part is, can you then survive? [If you do], you start to accrue an advantage that you’re not part of that same game.”

Katta’s approach offers a compelling alternative to the standard venture playbook — one that prioritizes resilience and coherence over rapid scaling, treating company culture and work environment as core product decisions rather than afterthoughts.

“Focus on doing your best work. The market will exist for you and others — it’s not always a zero-sum game,” he says.

Evening contraction

Katta closes his day as a reflection of how he begins — slowly and thoughtfully, but instead of reaching for energetic expansion, he unwinds in slow reduction.

At home, there are no overhead lights. Following research on how light angles affect circadian rhythms, Katta prefers warm, luminescent pools of light that allow his body to naturally wind down. He uses this space to gently pull on threads he’s curious about, whether that’s YouTube lectures, podcasts, audiobooks, or general reading or journaling on his Daylight tablet.

“I love wrapping myself in blankets at nighttime,” Katta says. “There’s something about just wrapping yourself with something fuzzy. It starts to put your nervous system into a calmer place.”

As his eyes grow heavy, a star projector casts grainy constellations across the ceiling. In the swirl of artificial stars, Katta finds himself in another liminal space — drifting between dream and reality, conscious thought and unconscious breathing.

Commitments to these spaces, to rhythm and restraint, to set and setting, are emblematic of Daylight’s products and experiences. They represent a different way of thinking about technology’s role in human life — not as an escape from embodied existence, but as a tool for enhancing it.

About the author

Jonathan Simcoe is a software designer and writer based in Portland, Oregon. He has published a children’s book about curiosity and written previously for Dwell.com. His work sits at the intersection of technology, design, parenting, and faith.