What comes next?

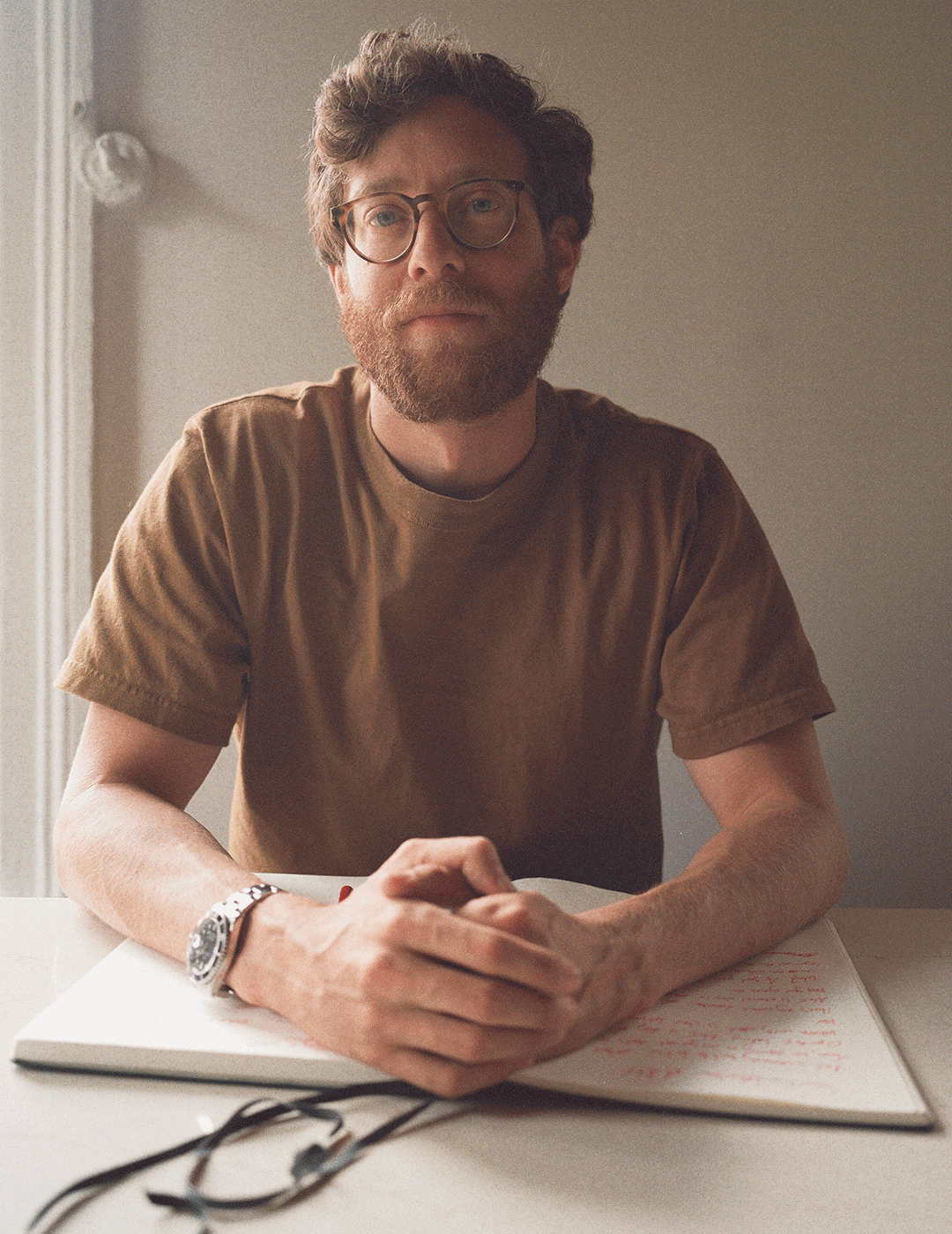

Dan Shipper, founder of Every, is betting on the emergence of the builder-writer, one who explores a topic through words, gauges response from an audience, and builds a piece of software from the insights gleaned. Shipper describes it as a writerly instinct — to see one’s words in physical form — that would have been near impossible to fulfill before AI. Historically, products have taken time to build, and they’re never guaranteed to sell. But if the costs of building a product are driven down with AI, the writer suddenly finds themselves with a new opportunity.

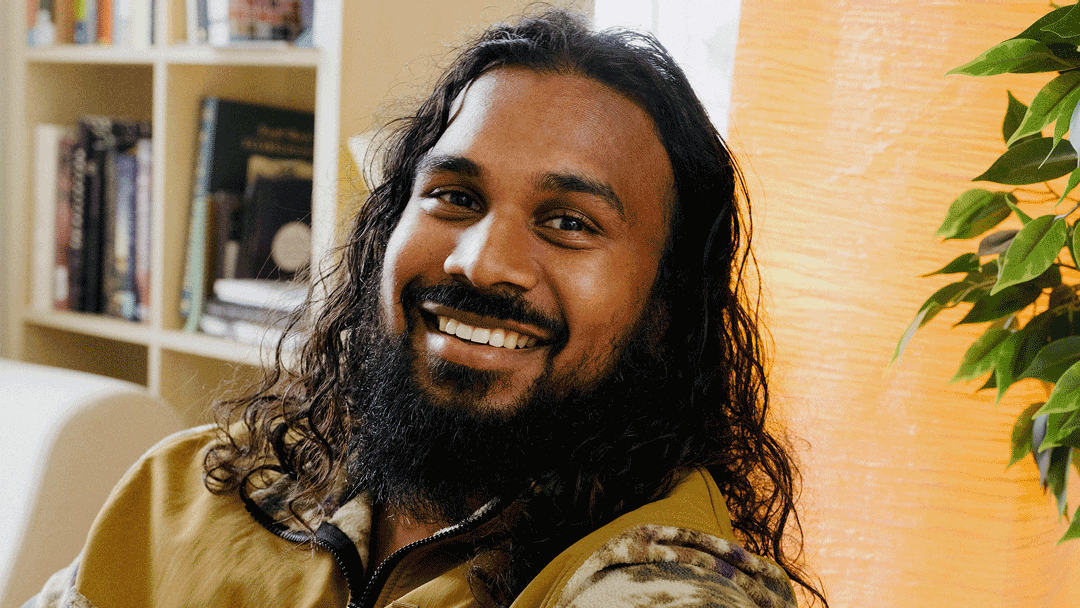

This is just one of Dan’s many theses that he’s experimenting on this year. We’re sitting in his office, one you might recognize if you’ve watched his popular podcast, AI&I. Large windows overlook a knotted, old beech tree, and warm-tinted cherry-wood panels line the floors. It’s a converted home in Brooklyn, with a thin, creaky staircase. I spot his coworker in the kitchen, typing away at a long table near the stove. Shipper and I migrate to what was likely once a living room.

This old building is really the only way in which Every feels like it’s from the past. The media company’s plan zigzags into the future, between domains like writing and product-building that Shipper describes as “previously Balkanized.”

Read more stories like this one in Meridian: Details — on the subtle choices that shape how ambition comes to life.

“I think the line between writer and builder is blurring. The line between writing and software is blurring. And I think Every is a somewhat unique expression of that.” Code interacts with writing, writing interacts with products. Every offers an annual subscription that includes daily writing on technology published on their website and their newsletter, alongside a bundle of AI products the company has built — Sparkle, to clean up desktop files; Cora, to sort through email; Spiral, to automate repeat content; and Lex, to assist with AI writing.

This, Shipper believes, is the media model of the future. But all of this isn’t built by a solo writer. The best work, Shipper implies, comes from a set of people brushing up against each other. As of mid-2025, Every employs 14 people in a mix of full-time and contract roles (including, at one point, me!) — writers, editors, product-builders. “We’re just a team of smart generalists,” says Shipper. “The writers are building, the builders are writing, and our designer, Lucas, is just an all-around genius.”

I think the line between writer and builder is blurring. The line between writing and software is blurring. And I think Every is a somewhat unique expression of that.

It’s an interesting new plan for a media company that’s helped them close a recent $2 million round led by LinkedIn’s Reid Hoffman and has garnered them $1 million ARR as of June 2025. What started out as a newsletter evolved into Lex, the AI writing app, and other apps unfolded from there. As Every expanded its editorial scope and footprint, the company began testing out conferences, courses, and vertical newsletters. The way Shipper unfolds the company’s plan, in a time when the future of people’s attention feels unpredictable, is akin to how one might prompt an LLM: he simply asks, “what comes next?”

“You know the popular saying, build something you might want? I mean, this is the logical extension of it. Watch yourself and your desires, and you’ll eventually build something that other people might want too.” What Shipper also believes is this: to know what comes next, you need to know where you come from.

We have an hour to talk, but a lot can happen in a Shipper hour; rarely does he hem or haw. He takes me through his New Jersey childhood with a precise, near-photographic memory of the moments that made him who he is today: his childhood dream to build Megasoft, the Microsoft alternative, how he first felt typing on a clunky Alphasmart keyboard (“insanely excited”), the emotions his first read of Annie Dillard evoked. “Incredible,” he says. “She has a way of talking about darkness and sadness with a sort of reality that I find so admirable.”

Growing up, Shipper was interested in everything — science, technology, literature. He dreamed of becoming a scientist and prototyping a technology that would let divers breathe in oxygen while they were underwater. But when tech founder stories entered the mainstream, he saw another possibility: “There was this shift in my childhood when all the media about scientists was replaced by tech guys. The trope of the inventor fell away to be the trope of the founder,” he remembers. “And then I wanted to be Bill Gates.”

As a teen, a Bill Gates biography taught him a lesson he keeps to this day: When there’s a new platform shift, like the personal computer, smartphones, or AI, there’s a lot to be built to serve that platform. So he tinkered on a few BlackBerry apps that he sold online. One located friends, while the other changed the colors on the LED behind the trackball based on the weather.

By the time he got to college at University of Pennsylvania, the iOS store had launched. He started to make apps for the iPhone, “and that was how I paid my way through beer and pizza in college,” he remembers. “Software was especially cool to me because you could make it once, and then just keep selling it to people, and you didn’t have to make it again.”

Shipper kept himself interdisciplinary. In some ways, entrepreneurship felt like an extension of his interest in science. “If you remember The Lean Startup stuff, it really treats startups like science. You’re supposed to have hypotheses, do experiments, invalidate the hypotheses. This kind of stuff really intrigued me.”

At university, Shipper studied philosophy. “I felt I wanted to know how to live a good life, and that was the only major that would tell me how to do it,” he says. Still, he hung out with technologists, computer science students, and other interdisciplinary thinkers who wanted to take the vaporous mass of their thoughts and turn them into reality.

With these friends, Shipper started a company known as Firefly. “It was a co-browsing software, which would let you share a webpage — like screen sharing, but not for the desktop.” By the time he graduated, he’d sold the company to Pegasystems for “several million,” flying from his “college graduation to Boston to negotiate the deal.”

By that point, a few themes had emerged for Shipper: he liked building software products that interacted with major shifts in technology. Charging for his work felt good. The generalist’s role, connecting all sorts of disciplines, felt like a good fit for him. Working with his friends was fun.

Most of all, he liked to write things down. “What was different, I think, about my experience, is that I was really writing down everything that I was doing,” he says. “I was publishing it, and this sort of got me a following online. I think that I was early to articulate what it meant to build a startup while I was building it. That made a huge difference for me, and also taught me the power of writing as a way to understand your audience.”

Watch yourself and your desires, and you’ll eventually build something that other people might want too.

When Shipper starts to tell me about his late 20s, he explains that they were less easy. “My mental health just got worse and worse, and I was working hard to fix it. I did everything you could think of — therapy, meditation, diets, retreats. Eventually, I realized I have OCD. It was undiagnosed, and it was really surprising to me, and it started to bleed into my work. Now that I’m on meds, I’m no longer in a 24/7 emergency, and my mind doesn’t wander as much.”

In 2020, Shipper went on to found Every with Nathan Baschez. “I wanted to build one of these tools for thought, like Roam or Notion, and I wanted to ask all these smart people about how they did it. And then I wanted to launch software for them. So I started a written series called SuperOrganizers, asking people about their processes. That blossomed into where we are today.”

The launch of OpenAI’s GPT-3 in 2020 catalyzed Shipper to go all-in on AI — writing analyses of the latest news, reviewing different models, and trying to build products. It was a new platform shift that Shipper didn’t want to miss.

In SuperOrganizers, which ran frequently from 2019 until 2023, Shipper interviews interesting people on the tools that shape their processes: how a head of growth did email, or a podcaster cleared their tasks for the morning. A year in, Shipper began to commission articles from external writers, expanding Every’s coverage to include news analyses. Deep dives into the latest on chain-of-thought unfolded, quickly, into takes on ChatGPT as a tool that could read past and future journals and provide insights into how Shipper might live his life.

“People have asked, hey, if we’re covering business and technology, why do we have all these articles about psychology? For me, it’s like — build who you are. You have to figure out who you are first to do that, and these pieces are part of that.”

Every’s products follow this editorial throughline as well, that there’s an engaged cohort of people interested in experiencing the future, whether it’s through writing or software, and that the best way to serve these people is to simply ask his signature question: “What comes next?”

In 2020, Shipper concluded, after interviewing a number of people for SuperOrganizers, that a useful tool would be one that could clean up desktops. He launched an early, pre-AI version of Sparkle, but it didn’t make a splash. More recently, he worked with Brandon Gell, one of his entrepreneurs-in-residence (EIR), to revamp it. As of April 2025, Sparkle had grown to thousands of users.

Shipper credits some of Sparkle’s success to improvements in AI, but he’s also clear that the company’s progress is aided by how it engages with its EIRs. “A big part of my plan with EIRs is to make sure the work they do actually sees the light of day,” Shipper says. “I spent some time at an incubator in my 20s, and really learned the value of shipping the products you ideate from them. New people can add so much energy to what you’re doing.”

EIRs aren’t required to use AI while building products, but all of them do, testing out new methods of working. It’s not just those working directly on products — all of Every’s staff use AI. “AI is one of those tools that really reflects the person who’s using it,” says Shipper. “We’re not prescriptive, but it is something we all use.”

This doesn’t mean Every is fully auto-generating pieces. Shipper believes that writing is like thinking. For him, using AI is like having a second brain that holds large amounts of his written work — articles, journals, emails — and thinks alongside him as he writes. Sometimes, it supplies metaphors that fit the ethos of the point he’s trying to make. Other times, it nudges him in a direction that he may not have considered, reminding him of something he’s mentioned in other documents and could serve to strengthen his argument. Still, rarely, if ever, does a piece get fully produced with AI.

Once a piece is written, however, all cylinders are go. Spiral auto-generates headlines, social media content, and copy from original texts. Summaries are sent to Every’s design lead, Lucas Crespo, who has developed an entire visual language using AI. His collage-like works extend Every’s editorial vision into imagery, often featuring Greek statues with their noses buried in books or with a chisel to their own faces. They pop up right before you read an Every article on their website, figures trying to understand themselves deeply, using what they’ve learned to improve what hasn’t been working, and charting a way to the future with what has.

As with any upstart hoping to take an uncharted path, Every faces large questions. I wonder about the balance between editorial and product-building, and whether the team struggles to stop the products, which have clear use cases, from cannibalizing the writing, which can, at times, be less decided, more like ambling through a writer’s brain.

This balance doesn’t seem to worry Shipper too much. In fact, he seems to believe that media is moving into a future in which plaintext must exist alongside software, and that the two will learn to co-exist in harmony. What matters most is that the two forms are saying similar things.

“Eventually, I want to create a sort of institution that teaches people how to live and work better with new technology,” says Shipper. “I love that tension between the seriousness of an institution and the carefree playfulness of a playground.”

But these future plans are still sketches. For now, Shipper and the team are focused on a single question to guide them: What comes next?

About the author

Janaki M. Rao is a writer and editor based in New York.