Truth decay

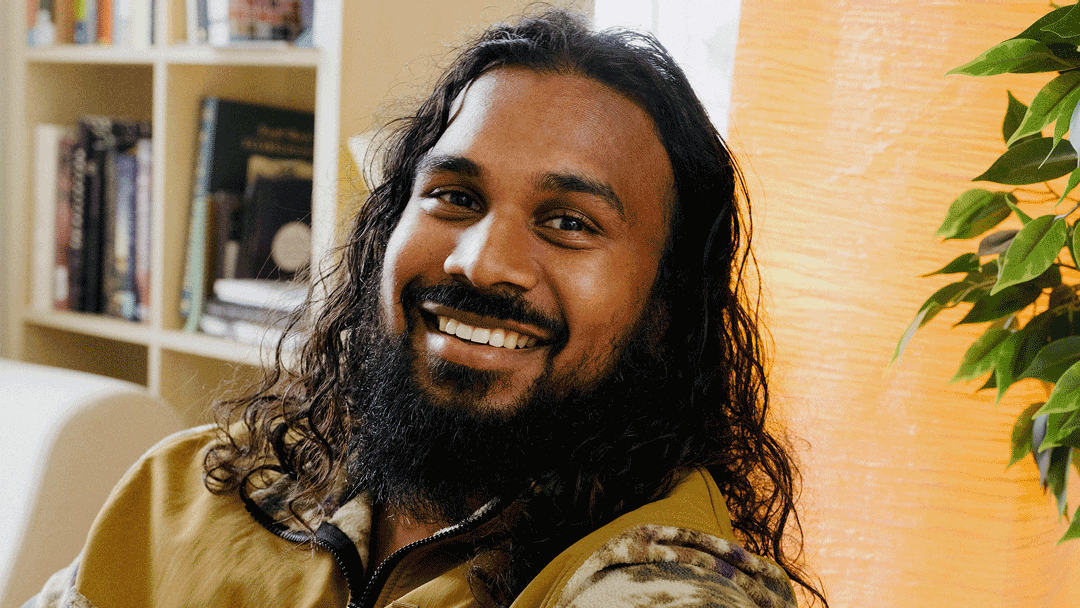

Sage Lazzaro is a technology writer and editor focused on artificial intelligence, data, digital culture, and technology’s impact on our society and culture.

In a since-deleted (or lost to the internet) Reddit post, a user shared an “inspo” photo of a moody kitchen they wanted to replicate in an upcoming remodel, and came to the forum for input on how to pull it off.

When the replies started pouring in, they weren’t about what tiles to pick or where to buy the sink fixtures. Instead, they zoomed in on the photo itself. It’s clearly AI-generated, said commenters in r/DesignMyRoom, pointing to subtleties in the image. The flowers melt into the sink. There’s half a stand mixer on the counter. Something about the cabinet hardware is just off.

Similar situations are playing out across the internet — in people’s workplaces, and personal lives — as the flood of AI-generated content online has them putting images, videos, and text under the proverbial microscope, looking for details like wonky hands (historically a tell of AI) or the excessive use of em dashes (which some claim is a hallmark of ChatGPT-generated writing) to distinguish between authentic and AI-generated content. But with AI models rapidly advancing, and their output becoming more mainstream and widespread, the strategy of treating the internet like a spot-the-differences puzzle is seemingly on its last leg. Much AI-generated content is becoming indiscernible to the human eye, and it’s only slated to get better — or worse, depending how you look at it. (In between this story being written and published, OpenAI released Sora, a text-to-video model which can create ultra realistic videos, bringing conversation about AI-generated deepfakes to a boiling point.)

As it becomes harder to know whether we can totally trust our eyes and ears, founders of companies like Reality Defender, Hive, and GetReal are building tools designed to detect AI content that might otherwise be indistinguishable from the “real” thing. The needs for this technology are wide-ranging, from currently deployed use cases like detecting insurance fraud to uncovering manipulated legal evidence so jurors trust what they see in court. For the founders, however, it feels like a higher calling. They’re trying to save our relationship with reality.

Read more stories like this one in Meridian: Details — on the subtle choices that shape how ambition comes to life.

When I met with GetReal co-founder and Chief Science Officer Hany Farid over Zoom, I started out speaking to a middle-aged man with salt-and-pepper hair and a wide grin, showing me his bike mounted on the wall behind him. About six minutes in, I blinked and suddenly was looking at someone else, a young man with black hair. I blinked yet again and found myself staring at OpenAI CEO Sam Altman… Or rather, a shockingly realistic deepfake of him. Farid, posing as these other men, demonstrated how startlingly deceptive the most realistic deepfake technologies can be. He waved his hand in front of his face, leaned on it, and turned his head from side to side to drive home the point. These subtle movements that until fairly recently could potentially expose a deepfake did nothing to reveal his scheme. And through it all, the bike was still there, unchanged. He switched back to himself, but was it ever even really him?

Farid’s demo was sandwiched between impassioned speeches about the dire risks posed by deceptive AI content (including material involving the sexual abuse of minors, business fraud, criminals extorting families for massive sums of money, and more) and how, in an era where disinformation and conspiracy theories are already running rampant, AI-generated content can “[threaten] our whole sense of reality.” He’s been thinking about how digitally manipulated media could be used to deceive since 1997, when he was an academic embarking on what would become a lifetime of research into digital forensics, misinformation, image analysis, and human perception.

“I was focused on the law, like thinking about evidence and courts of law. And so I started thinking about this problem and publishing a few papers. And by the way, the field didn’t exist, and for good reason — this wasn’t a problem [at the time]. But it felt like it was going to be a problem,” said Farid, who is widely regarded as an expert on deepfakes and manipulated media and continues to work as a professor at The University of California, Berkeley.

He switched back to himself, but was it ever even really him?

For decades, it was a slow burn. Farid was sometimes called to serve as an expert witness in court cases. Occasionally, he’d get calls from intelligence officials or a news outlet looking to verify the authenticity of digital images — like a now-infamous doctored photo of Kim Jong-il released by North Korea. The rise of Photoshop, social media, and early deepfakes in the 2010s inched the needle, but hardly. Then came the large language models.

“Honestly, I just became overwhelmed,” Farid said, explaining why he started GetReal, which offers solutions for detecting deepfakes and preventing AI-enabled “impersonation” attacks. “I used to be able to handle the cases. AP would call, Reuters would call, the FBI would call, a parent would call — whatever it was. And it was manageable. And then suddenly it wasn’t. I mean, no kidding, I get multiple calls a day. Every morning I wake up and we’ve already got 50 emails from reporters… Generative AI just completely changed the ball game.”

Today, Farid is hardly alone in his field. A 2024 Insight Partners report projects that the deepfake AI detection market — which was valued at $213.24 million in 2023 — will grow at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 41.7% through 2031. A host of startups in the space have cropped up, commercializing technologies to help businesses and everyday people wade through the sea of AI-enabled deepfakes, fraud, misinformation, and internet slop. Even enjoyable content and creative works made in good faith are caught in the mix — all with the aim of establishing a shared baseline of knowing what’s human-made and what’s not.

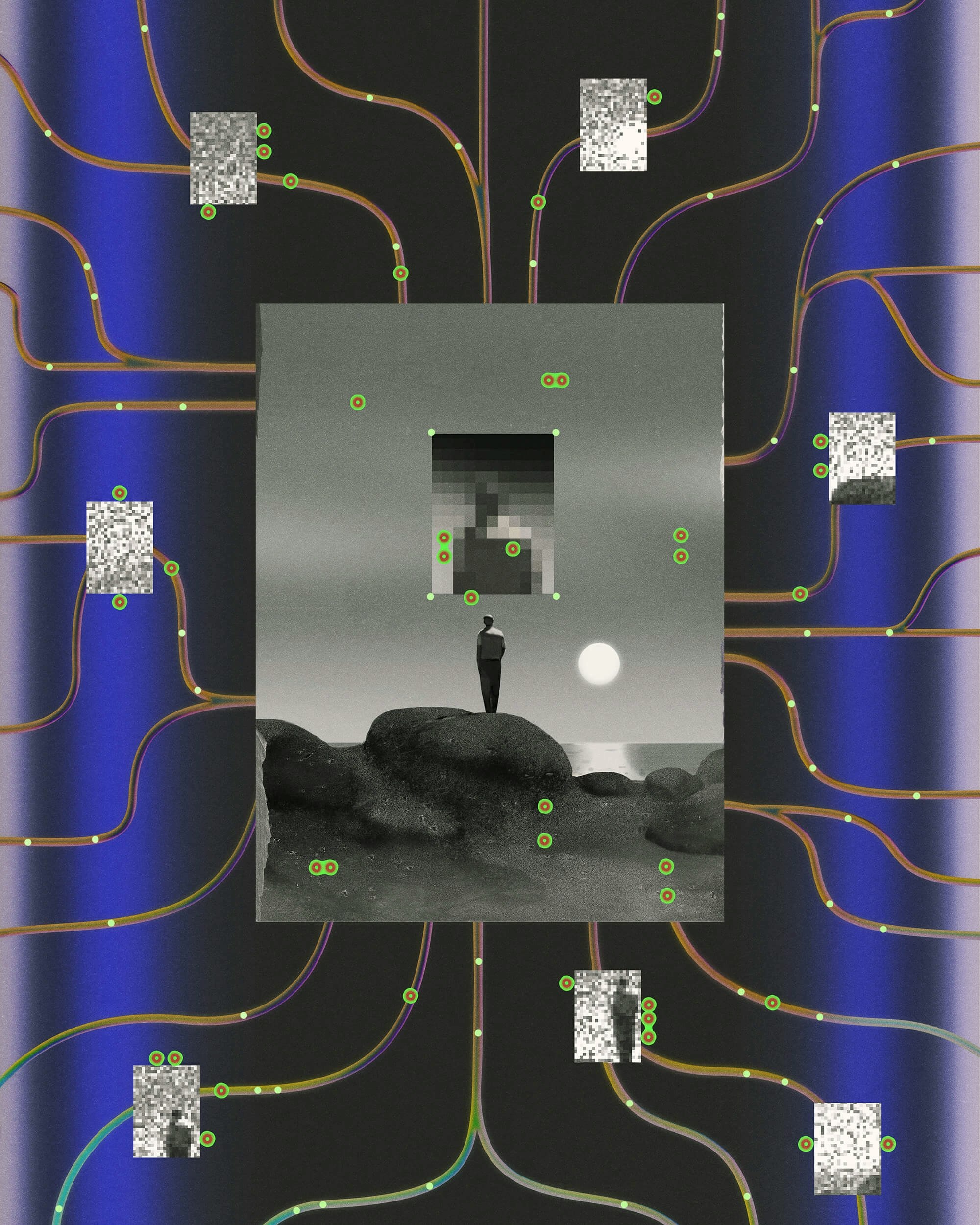

Currently, companies and platforms are generally approaching the problem in two ways: by creating methods to label or embed a small detail — a watermark, label, verifiable metadata — into content to prove it’s not AI-generated, or by creating tools to analyze content and determine if it is AI-generated.

On the former, these efforts have largely coalesced around C2PA content credentials, which are an emerging open technical standard for metadata often described as a nutrition label for digital content. The idea is that anyone can view the metadata and see if content was created or altered with AI, but the method has flaws, at least for now. It only works if creators proactively apply credentials — and even then, the metadata can be altered or removed fairly easily.

On the latter, companies creating technologies designed to evaluate content are typically using AI and machine learning models themselves to scan photos and videos at the pixel level, detecting patterns and small details, considering lighting, physics, geometry, reverberation in audio, and more — things that may now be too subtle for most people to catch.

“When you look at an image, you’re looking for perhaps obvious oddities, right? So maybe there are like six fingers or that that object looks a little bit misshapen or that seems out of place,” said Kevin Guo, co-founder and CEO of Hive, one of several companies commercializing this tech. “The problem we have now is a lot of these models are getting really good at making things look realistic. And so the differences in the content are starting to actually escape out of human eye resolution.”

... the strategy of treating the internet like a spot-the-differences puzzle is seemingly on its last leg.

Guo’s founder story is straight out of Silicon Valley. He studied at Stanford, started a video chat app with a classmate shortly after graduating in 2014, and then pivoted the business to content moderation after realizing the models they created to keep problematic content off their platform were actually their big winner. In late 2022, they expanded their moderation services to tackle AI-detection. Guo said the majority of Hive’s research efforts are now dedicated toward this problem, which he calls “existential.”

In 2024, The U.S. Department of Defense signed a $2.4 million contract with Hive to support the intelligence community in detecting content and misinformation that’s been artificially generated or manipulated using AI. For the everyday user, the company has a free Chrome extension that allows people to copy and paste images into a box and get a determination of whether or not it was generated by AI — an unproven but well-intentioned attempt to give users peace of mind. For Hive and the other companies creating these solutions, however, much of the business revolves around corporate clients, from insurance companies trying to avoid fraudulent claims to any enterprise trying to ensure their employees don’t fall for deepfake social engineering attacks. One example: an employee at a multinational company who was tricked into transferring $25.6 million of the company’s funds to malicious actors who used AI-generated deepfakes to pose as the CFO and other colleagues on a video call.

Beyond imagery, there’s text-based content to consider, too. There are now platforms that claim to be able to detect if text was written by AI, which have become a go-to for various professionals and especially teachers trying to determine whether students are outsourcing their homework to ChatGPT. These tools typically analyze factors like word variation, flow, sentence complexity, and the use of clichés to evaluate text and offer an AI percentage (for example, determining a paper was 90% written by AI).

But compared to the technologies scanning for pixel-level details in images, videos, and audio, evaluating text in this way is an imperfect science. The writing styles of those who are neurodivergent, non-native English speakers, or just less “advanced” in their writing may resemble the patterns AI detectors consider as signals of AI content. One study by Stanford University researchers, for example, found that AI detectors flagged more than half of essays written by non-native English students. That group — the fastest growing student population in the U.S. — was disproportionately labeled as producing AI-generated content.

Across the internet, students who are facing disciplinary action for plagiarism after their work was flagged by an AI detector are frequently asking for help proving their innocence, as they’re often left with no recourse despite the evident fallibility of these tools. And the proven issues with the current products haven’t stopped teachers from heavily using them: 68% of teachers reported using these AI detection tools in the 2023-24 school year compared to 31% the year before, according to a survey published by the Center for Democracy & Technology. That study found a 61.3% false positive rate — highlighting how often these tools falsely accuse students. Overall, it represents just one way the general lack of guidelines, regulations, and consensus about how to deal with AI is already having serious, widespread consequences.

In addition to developing technologies to preserve our reality, some founders have taken their concerns about the lack of AI guidelines before lawmakers.

Ben Colman, co-founder and CEO of Reality Defender, testified in front of a congressional subcommittee in 2024 on the dangers AI could play in elections, stating that deepfakes “are especially troubling in how they can fabricate a new reality for a person or millions of people.” Guo recently presented in a California committee hearing focused on detecting AI in political ads. Both Guo and Colman have publicly supported legislative efforts like the the “NO FAKES” Act, a bipartisan congressional bill to protect the voice and visual likeness of all individuals from unauthorized recreations made with AI, and the “DEFIANCE” Act aimed at combating non-consensual deepfake pornography. And Colman’s firm even recently launched a free “legislation tracker” to help the public track the growing number of deepfake-related bills.

If there’s any question about what Colman is trying to achieve, his firm’s name — Reality Defender — says it all. Talking to him, it’s clear he is driven by a sense of morality, repeatedly referencing morals, ethics, and what type of world he wants his kids to grow up in. His career has spanned data and identity security and privacy, a way, he says, to work in tech while upholding his morals around protecting people from the various harms of cyber crime.

But today, the lines between our online and offline worlds are entirely blurred.

While his company is also in the business of AI-detection tools, Colman says regulation is as important as any tools and services when it comes to the mission of preserving reality. He believes legislation must move as fast as AI, which is being built by companies that “move fast and break things.”

“Unlike the apps and startups who followed such a motto before them, the ‘things’ in this instance,” Colman said in his congressional testimony, “are aspects of society everyone in this room holds dear: democracy, truth, trusting what you see and hear.”

Perhaps the trickiest aspect of trying to navigate the flood of AI-generated content — and the downstream impact of not knowing what’s “real” — is that it’s leading some people to doubt factual content and information, too. Even as tools are emerging that may eventually shift this, people still have the ability to dismiss anything they don’t like as AI-generated. For a highly visible example, President Donald Trump claimed in February 2024 that an unflattering photo of him playing golf was altered with AI, and later turned the tactic on his 2024 election opponent, former Vice President Kamala Harris, falsely claiming the large crowd at a Harris rally was AI-generated. Knowing that AI-generated content can be both incredibly believable and difficult to detect can lead some to feel the need to question everything and everyone.

“I think for a long time there was a sense of: ‘It’s a bunch of pixels. It’s digital. It doesn’t matter,’” Farid said. But today, the lines between our online and offline worlds are entirely blurred — and it all matters. As AI technology advances and the real becomes harder to discern, the impact on our collective sense of truth and trust is palpable.

“Most of our world is spent on this, you know, 10-by-10-inch screen that we live on. We reason about the world, right? We make decisions based on this,” he added. “And suddenly, everything you read, see, and hear is suspect.”

About the author

Sage Lazzaro is a technology writer and editor focused on artificial intelligence, data, digital culture, and technology’s impact on our society and culture. Her work has appeared in Fortune, VentureBeat, Business Insider, Wired, Supercluster, The New York Observer, and many more places

Related reads

What comes next?

If the devil’s in the details, the robots are too