If the devil’s in the details, the robots are too

Elizabeth is a writer and dreamer based in San Francisco.

We’ve all seen them. Many of us live in them. And while some of us find them unfortunate, there are many of us who find them perfectly desirable.

It’s the cookie cutter. The pre-fab. The sprawling, single-family American housing developments whose uniqueness stops at the chosen color of stucco, the mild distinction of a three-car garage. Inside, you’ll find the open-kitchen floorplan. The finished basement that may or may not feature an at-home movie theater, complete with soft leather recliners and an old-fashioned popcorn machine that does little but catch dust.

These houses feel like they were made on an assembly line — and that’s because in some ways, they were. Despite the appearance of personalization, they are largely detail-less. Yes, you can choose from one of five floor plans, the finishes in your ensuite bathroom, or the style of your front door — but this is merely the illusion of bespoke detail, hardly different from visiting the auto dealership and opting for brown seats over black.

Read more stories like this one in Meridian: Details — on the subtle choices that shape how ambition comes to life.

Whether you appreciate the utilitarian or aesthetic nature of a “cookie cutter” neighborhood is a matter of preference and personal taste. But typically, it would be difficult to argue that the bones of these homes are unique, let alone expertly detailed according to the homeowner’s preference, despite the homeowner having built the home, or having made aesthetic decisions for the home prior to its construction.

One stroll through a neighborhood like this and we’re reminded of something that can feel instinctively true: scale — as applied to objects or aesthetic experiences — and intentional, artistic detail can almost seem at odds with each other.

The common sense reasoning goes: If something is produced on a mass scale and sold at a lower price, it is unlikely to be high quality. It’s also unlikely to be detailed enough or interesting enough to qualify as “craft” according to our intuition. (David Pye’s The Nature and Aesthetics of Design is something of a classic read on this front.)

Many Americans would probably agree that a lot of things — from buildings to furniture and clothing — are, at least anecdotally, not as ‘good’ as they used to be.

But as I write these words now, there are many hardworking people trying to create a world where scale, affordability, and craft are not mutually exclusive. The sort of elevated craftsmanship you’d like for that new house you’re building, for example — but which has been, up to this point, squarely out of budget — could wind up within reach sooner than you realize.

The unlock here is artificial intelligence, which is widely expected to significantly reshape our world in the coming decades — including, potentially, how we perceive “craft” and incorporate it into our everyday lives.

What remains to be seen is whether — and on what terms — those who pride themselves on valuing “true craft” will be keen to accept it.

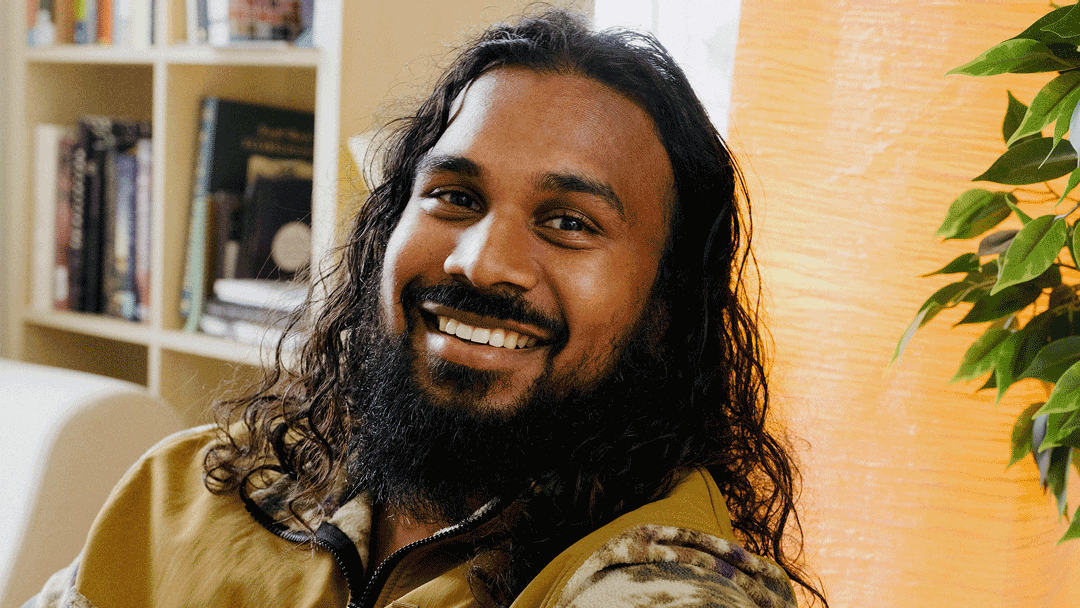

“I always wanted to be an architect,” says Micah Springut. “But I didn’t want to be an architect in 1990 or 2000. I wanted to be an architect in 1910, or 1890.” Back then, he continues, “architecture [was about] using beautiful materials to create beautiful things for the public. But [over the course of the 20th century, with the introduction of mass-produced building materials], we got far away from that… Craftsmanship really just disappeared from our building lexicon.”

Springut is the founder and CEO of Monumental Labs, a New York-based startup seeking to revive stone craft through AI-enabled automation. In his team’s words, the company is “building an AI-powered robotic fabrication platform” that seeks to “bridge the workshop traditions of fine arts with cutting-edge technology to make magnificent sculpture and stone architecture accessible at scale.”

The goal is to reduce the costs of stone fabrication up to 90%.

This, Spingut says, will be made possible through the development of software and hardware that automates the most expensive and time-consuming parts of stone fabrication.

“If you can make [stone craft] cheap enough… you can bring back craftsmanship into our buildings and our architecture. Monumental Labs is one big experiment to see if we can do that — and so far it’s working.”

Scale — as applied to objects or aesthetic experiences — and intentional, artistic detail can almost seem at odds with each other.

Many Americans would probably agree that a lot of things — from buildings to furniture and clothing — are, at least anecdotally, not as “good” as they used to be. With the passing of every season, we see new microtrends from fashion to interior design spreading like wildfire on platforms like TikTok. But at the same time, more people are voicing frustration not just with the poor quality of fast, budget-friendly items, but also with the disappointing craftsmanship of products of all types marketed as premium — and priced accordingly.

This phenomenon extends to building materials, whether someone is giving their home a facelift, a mid-sized American city is building a new elementary school, or real estate developers are breaking ground on the next mixed-use apartment complex in your rapidly gentrifying neighborhood.

“[The vast majority] of buildings are just the cheapest, junk panel systems you can buy from China and affix to the side of a concrete wall,” says Springut. “There’s very little architecture going on, though so-called architects are designing [these things].”

“The cost of building today versus what it was at the turn of the century is about five times more expensive — and that’s accounting for inflation,” he says.

Listening to Springut lay out the possibilities enabled by technologies like the ones Monumental Labs creates, he seems to be advancing the idea that artificial intelligence has not only the capacity to move us into the future and usher in unprecedented innovation, but also to restore some of what has been lost in our age of profit-at-all-costs mass-industralization. This is a world, he posits, in which quality building materials and expertly crafted detail are not cost prohibitive. This is a world in which anything you want to create with stone, you can — thanks to automation. And as a result, this is a world in which some of history’s most revered architectural styles can not only be revitalized, but built upon for the sake of creating new and different beautiful things that aren’t following the 21st century status quo of maximizing what you can build with as little human intervention as possible.

“We’re not just leading a technical revolution,” he says. “It has to be a craft revolution too — and one that is tasteful.”

It’s clear Springut knows to anticipate my next question, which feels like the natural follow-up to any talk about robots: What happens to artists? Will stone craftsmanship, as a human profession or specialty, inch toward obsoletion?

“We’re not replacing artists. We’re not getting rid of craftsmen. We’re actually expanding the market for them,” he responds, by making their work easier to produce and more readily available. “We have human designers, we have human artists, we have human carvers — the robot is simply a tool to help us do this cheaper and faster.”

Monumental Labs isn’t the only company with a vision for craft at scale. For example, Artaic, a Boston-based tile design studio, is also using AI-powered technology to democratize another painstaking ancient art form: mosaic. Founded in 2007, well before today’s AI boom, Artaic combines advanced design software with robotic assembly, enabling fast, custom, and American-made mosaic tilework that blends artistry with precision.

Similarly, the fashion industry — which, at least in some corners of the industry, places high value on human-produced craft — is poised for AI-driven disruption. For example, Los Angeles-based startup Blng, an AI jewelry design app, gives users the ability to turn sketches, photos, or even keywords into photorealistic jewelry renderings in seconds — drastically shortening the design-to-presentation timeline, which makes it easier for creators to visualize and iterate on their ideas. Founded in 2023, it gained traction quickly, raising $3M in funding and earning the LVMH Innovation Award, opening the door to a collaboration with Tiffany & Co.

Just like Monumental Labs, both Artaic and Blng are adamant in their positioning around human-robot collaboration. Like Springut, Dumëne Comploi — Blng’s co-founder — believes that technology should empower creatives to make better art. It’s not a replacement for the artist. It’s a tool.

Will we still see something as ‘craft’ when we know that a robot played an instrumental role in bringing it to life?

The art world has heard this argument before. Rather than see AI as the enemy, commentators across the internet have argued that creators should work alongside technology, rather than against it — especially if it enables us to “expand our creativity” or do more, faster. Contrary to the common adage that constraints breed creativity, this philosophy posits that creativity is at its best when there are no constraints. It is also based on the premise that more is always better than less, or that more items with complex detailing (not easily created via human hand) are also logically more impressive. What it doesn’t take into consideration, however, is that “more” of something can also cheapen that thing or depersonalize it. In the case of traditionally human-made crafts, this consideration feels especially pertinent.

When all of our buildings — including our homes — can be decorated by a custom stone facade, are we more or less likely to appreciate that facade? Will we still see something as “craft” when we know that a robot played an instrumental role in bringing it to life?

Evolving technologies make it increasingly possible for detail and scale to live in harmony with each other. But whether that newly enabled level of detail at scale is viewed as meaningful, impactful, or valuable is another question entirely.

It’s true that many of us won’t even be able to tell the difference between what’s primarily human-engineered versus AI-engineered — something already illustrated in the world of 2D art by a striking 2024 survey from psychiatrist and writer Scott Alexander, who asked readers to identify whether various images were created by humans or by AI (according to Alexander’s findings, 40% of humans mistook each AI picture as human-crafted). But we’d be remiss not to wonder what effects AI-driven advancements in craft-related industries might have on our perception of craft itself.

Of course, there will be levels to this. What someone is willing to put on the exterior of their house, for instance, might be different from what handbag catches their eye on a luxury resale site. More Hermès Birkin Bags on the market, for example, does not necessarily spell more commercial success for Hermès — a brand that has long relied on strategic scarcity to maintain its exclusivity and mystique. “Keeping up with the Joneses” social dynamics could take on a new dimension as craft and luxury customization becomes — depending on the specific product — either more desirable or veering into cliché.

As for now, concerns that a company like Monumental Labs could trigger a wave of Las Vegas-style, craft-imitative pastiche seem exaggerated. For one, highly skilled artists are the main drivers of anything the company produces. Secondly, so much of what we willingly accept for architecture today is already mass-produced and “fake.” From river rock on someone’s chimney to the forest green turf we accept as lawn — we are already living in the world of postmodern houses, tilework, fashion, and jewelry, so what’s the harm in a little more? Or maybe, if things go according to Springut’s vision, the introduction of services like those that Monumental Labs provides will actually leave us with substantially less “tacky” and “ugly” in our surroundings than we’ve seen over the past 100 years. Technologies like these might actually enable us to enter that “golden age of art and architecture” that the people at Monumental Labs envision.

Detail at scale won’t appeal to everyone. Not soon — and maybe not ever. What people choose to accept or appreciate as “craft” (human-made, human/robot-made, or robot-made) will vary person to person. Hearkening back to the cookie cutter, there are people today who want a home they don’t have to think about, who buy the art for their living room at The Home Depot. But before we put this hypothetical person in the category of not appreciating “true craft,” they may also be the type of person to hand-knit all of their sweaters out of preference. They may only buy handmade jewelry from small business owners on Etsy. Or maybe they love nothing more than their meticulously built outdoor kitchen with its imported firebrick pizza oven.

Personal taste isn’t always consistent — we’re choosy in some domains, indifferent in others. We’re all emotional, idiosyncratic, and often gloriously contradictory, and that’s part of what makes taste (and our relationship to craft) so personal. Even on the societal and community levels, the nuances of taste are also greatly subject to diverse influences and difficult to predict.

Likewise, there will be those resistant to any type of machine-engineered mosaic in their homes, for instance, but these very same people could be more than happy to see the same mosaic at the post office in lieu of the boring white wall that could have been.

We’re all emotional, idiosyncratic, and often gloriously contradictory, and that’s part of what makes taste (and our relationship to craft) so personal.

Perhaps more interesting is the opportunity these AI-enabled, craft technologies present in reshaping the connotations we have around something that is pre-fab, manufactured, or otherwise made with machine help.

“There is a natural conservatism to people these days because I think they’re afraid of what ugly building is coming next,” says Springut. “But now, we can get back to an age where we don’t dread development and actually look forward to the beautiful things we can build.”

Does a machine whittling away at a block of stone, followed by an expert craftsman adding the final touches, compare to Michelangelo — and all the people who helped him — turning a block of marble into the David?

Probably not. But if we see craft at scale as the practical path to a more beautiful world — maybe it doesn’t have to.

About the author

Elizabeth is a writer based in San Francisco, whose work explores everything from nostalgia to the role of aesthetics in everyday life and the ways technology shapes our perceptions.