How I CEO: A community conversation

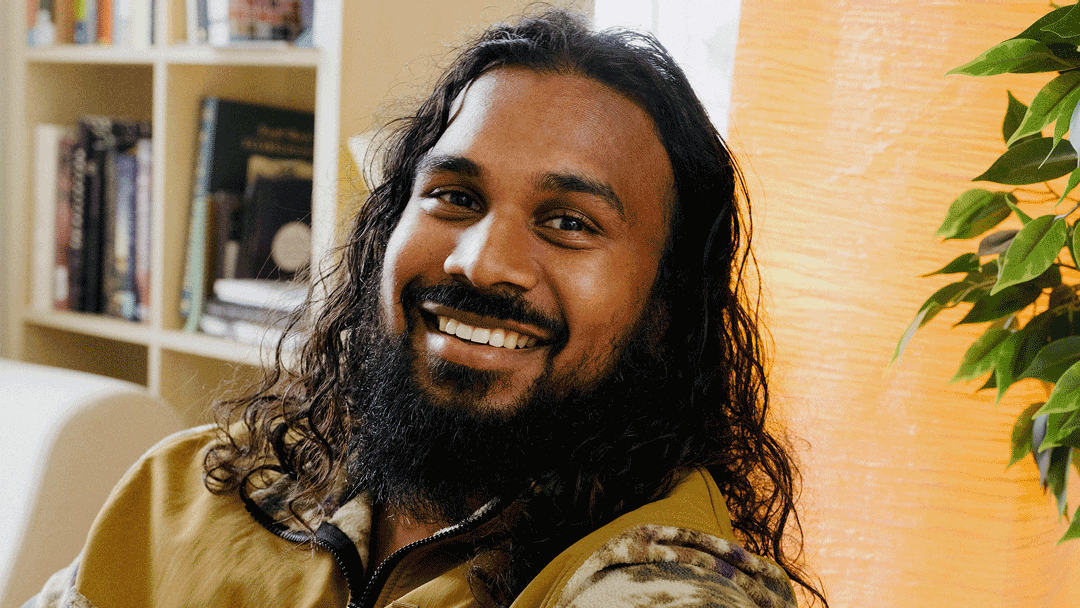

Co-founder and CEO of Mercury.

Over the next few months, I (Immad Akhund, CEO of Mercury), will share my stories, learnings, and tips for other leaders based on what has worked for me. I started my entrepreneurial journey 16 years ago as a recently graduated engineer and have had to learn all the “CEO” lessons the hard way — often feeling like I was making it up as I go. How one leads as a CEO is extremely dependent on any number of factors, like your style, your company, your stage, or your industry. Rather than taking these ideas as ones to copy verbatim, take them as food for thought — one example to learn from amongst the many.

At this year’s TechCrunch Disrupt in San Francisco, we hosted a series of Expert Sessions offering advice to startup founders on building and scaling their companies. My session covered navigating advice as a CEO (a topic I’ve explored in this column before), then tackled questions from the community on topics CEOs and founders deal with every day. Here, I’ve summarized and synthesized some themes from the Q&A to share with you.

On co-founder dynamics

Who your co-founders are is one of — if not the most — important decision you might make in the early days of your company. I’ve had varied experiences here, and after the first two companies I founded, I decided to only pick co-founders I’d already worked with. (For example, I’d worked with Jason and Max for five years before we started Mercury.) That experience helps you establish whether you work well together. It’s quite an intense relationship — you want to get it some version of right.

At Mercury, we set boundaries around what each co-founder owns and cares about. One co-founder is CTO and owns engineering, another owns product and design, and as CEO, I own everything else. Setting these boundaries makes working together fundamentally easier — if there’s disagreement, you can say “Hey, I don’t agree, but this is your responsibility.” It gives each co-founder room to run.

For any elements of business strategy that come up but no one owns, having the CEO as the end decision-maker generally helps resolve things. I’m not an unemotional person and I’ve always been very unemotional about business — I find the worst arguments happen when people get emotionally invested in an answer and are angry if the outcome isn’t what they’re invested in. I think if you can avoid that, you can generally have a pretty productive relationship with most people you work with.

On series A fundraising

Series A is an interesting point — you’re in motion but there’s still lots to prove out. Most series A investors make two or three investments a year, so it’s a big deal for them to invest in you. I find it works better if I have a relationship with them prior to making a pitch — expecting someone to shell out $10 million in a two-week period when you’ve just met is asking a lot. But, in my view, you shouldn’t pitch them before either of you is ready, either.

I’ve historically taken a bit of a long-term approach here. About nine months before I’m planning to raise, I’m having coffee meetings with investors — not pitching, just getting to know them, understanding what excites them. Obviously, I’m explaining what I do, telling them a bit about the company, but I don’t talk numbers, I don’t make it a pitch, there are no slides. It’s purely relationship building. If you’re going to be raising, ideally you’re doing this every six months for the two years before your fundraise, talking with and feeling out maybe 20 series A investors.

This will mean that once actual fundraising time comes, you know who to talk to, who’s excited about what you’re doing, what their objections to it might be — and, importantly, you have a good understanding of who they are.

Personally, I try to get fundraising done in three weeks. Before the three weeks, I prepare the deck and data room and refine the story — the usual. Then, the first week I met with friendlies to practice the pitch. The second week I meet with good investors that aren’t necessarily my top five to ten targets — doing maybe 15 conversations. And the third week I’m meeting with top targets. That third week, I’m talking to the eight or so people I’m really excited about, and hopefully these conversations are leading to other meetings and driving to a close.

Doing it this way is a lot of intense work and stress, but I find that once you do this in a very compressed time period, you build a lot of momentum and get a lot more confident in your pitch.

On ‘founder mode’

Founder mode has been on everyone’s minds quite a bit lately, but I’d say it isn’t really applicable to companies with less than 50 employees. At that point, you’re in your own version of founder mode by default — and if you’re not, you’re doing something really weird! I think the idea of founder mode becomes more relevant once you have scale — managers, middle managers, the like. That’s when founders and CEOs can get really detached from details, and when you can become a serious bottleneck.

If every single release needs your approval, you’re actually not deep in the weeds of it all — you’re very high level and just stamping a bunch of things. You’re probably spending all your time in meetings just saying, “This is good, this is not good.” You’re probably not stepping back to ask, “What’s the most important thing at this company?” You’re probably not saying, “How do I dive all the way into the real details to solve it?”

My interpretation is that founder mode is very much in line with going deep on specific problems that need your hands-on attention and your superpower, whatever it is. Creating good structure in your company can help people self-manage everything else.

On hiring, delegation, and trust

Maybe this is obvious, but it’s always worth restating: Hiring is really hard! And sometimes startups compromise too much just to get it done. It’s very easy as a founder to think, “Oh man, this is too much work. I’ve already spent two months hiring for this role. I’ll just pick this person even though they’re not perfect or there are some red flags.” I think that if you actually want to keep a very high hiring bar and you really can’t find someone, it’s better to consider going more junior than compromising otherwise. It’s critical to choose high potential people you can really trust — part of why some leaders don’t delegate is because they can’t trust the people underneath them, and that’s a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy or cycle.

If you hire good people, things can swing another direction. I tend to deliberately over-delegate, giving tons of responsibilities and forcing people to rise up to the challenge. Sometimes they can. Sometimes they can’t. If it’s the latter, you need to figure out if they’re wrong for the role or maybe you just need to hire someone over them. If it’s the former, you’ve got an incredible win.

On resolving product delays

When a team has a lot going on — they’re supporting the product, squashing bugs, navigating customer feedback — and then you tell them “go ship this other new big thing,” that’s when the biggest delays tend to crop up, in my experience. You wonder why something isn’t shipping, but if you talk to the team, they’ll tell you — while sweating bullets — that they just received five urgent bugs they have to fix. Okay, go ahead and fix the bugs! It’s necessary to address the issues, but if you don’t have the right plan in place to make it possible, you wind up starving out work on the new thing in exchange for incremental progress on the existing thing.

What we do at Mercury to avoid this is make sure there’s either a team or, say, a pair of engineers, that are just dedicated to the new thing no matter what. They’re not interrupted for bugs and the like unless there’s some kind of massive existential emergency. Having dedicated, focused resources like this can make a huge difference in your team’s ability to actually ship on time.

I also think there’s a bit of tendency on technical projects to over-engineer upfront, going down rabbit holes and trying to make everything absolutely perfect. Sometimes it’s worse when you’re a little bit successful already because you worry that the next thing has to be just as good and polished as the last thing, but that’s not always the case. You have to define what’s a must have and what’s experimental, scope it down, and decide when and whether to say, “This doesn’t need to be perfect.” You know the minimum set of features, and where the bar has to be incredibly high, and where there’s room to ship faster and iterate later. Break down every project into that and be consistent in doing so. Then press on, have urgency, and focus on the problem you’re solving and getting that solution to customers.

On competition

It can be a spicy topic, but mostly I think you shouldn’t worry about competition. In my 17 or so years of doing startups, there’s always been some competitor that’s raised a bunch of money, seems hot, is launching lots of things. It’s never really mattered. Most of the time companies are doing well or not based on their own merits. If they’re not doing well, often no one in the market is doing well, or they’re just not doing a good enough job for customers.

Customers will help you learn about competitors, but through their own lens, which is probably the most important lens for you to look through. They’ll tell you they need a feature, and when you ask why, they might mention a competitor has it and it looks good or someone else they know is using something like that. Listen to customer, not the competitor noise — focus on creating what you think you should do to solve their needs, not having your roadmap determined by competitors.

Find more events and upcoming expert sessions (in person and virtual) at events.mercury.com.

About the author

Co-founder and CEO of Mercury.