Demystifying fintech account structures: Demand deposit accounts (DDAs) vs. for-benefit-of (FBO) accounts

It’s rare that you’ll want to know the innermost workings of your bank or banking provider. In most cases, the main things you’ll care about are that your money is safe, and that you’re able to move or access it reliably. But in some moments — and particularly in moments of uncertainty — there’s peace of mind in knowing how things work; in having all the facts so that you can make informed decisions about how and where you store your money.

Understanding the distinctions between demand deposit accounts (DDAs) and for benefit of (FBO) accounts is one way to achieve this peace of mind. Each type of account has specific implications about the type of relationship an end-user has with their bank, the level of ownership they have over their account, and their insurance eligibility. Knowing these core differences can help you navigate your own banking relationship with more confidence.

Key takeaways

- DDAs give end-users a direct relationship with the bank, whereas FBOs involve a third-party intermediary, like a fintech.

- DDAs have direct FDIC insurance up to $250,000 per depositor (subject to aggregation rules), while FBOs may have "pass-through" insurance if properly structured. There are also special cases with types of custodian accounts, such as sweep network structures, where funds are only eligible for pass-through insurance.

- Neither DDAs or FBOs are inherently safer — both are subject to traditional regulatory compliance, and potential layers of fintech-specific compliance, depending on the setup.

What is a DDA?

A demand deposit account (DDA) is a type of bank account where the end-user has direct ownership over the account — in other words, what you’d commonly think of as a checking or savings account. (The jury — or in this case, financial authorities — is still out on money market accounts, which are sometimes classified as DDAs and other times not).

An important qualifying feature of a DDA account is that it’s highly liquid, providing easy access to funds through various means such as checks, debit cards, and electronic transfers.

What is an FBO?

An FBO — meaning “for the benefit of” — could actually refer to a few different types of accounts, particularly because it’s not a strict regulatory term but rather a general industry term that can have a bit of nuance. That said, the common factor is that it refers to a model where there’s an intermediary, such as a fintech, that holds an account on behalf of its customers.

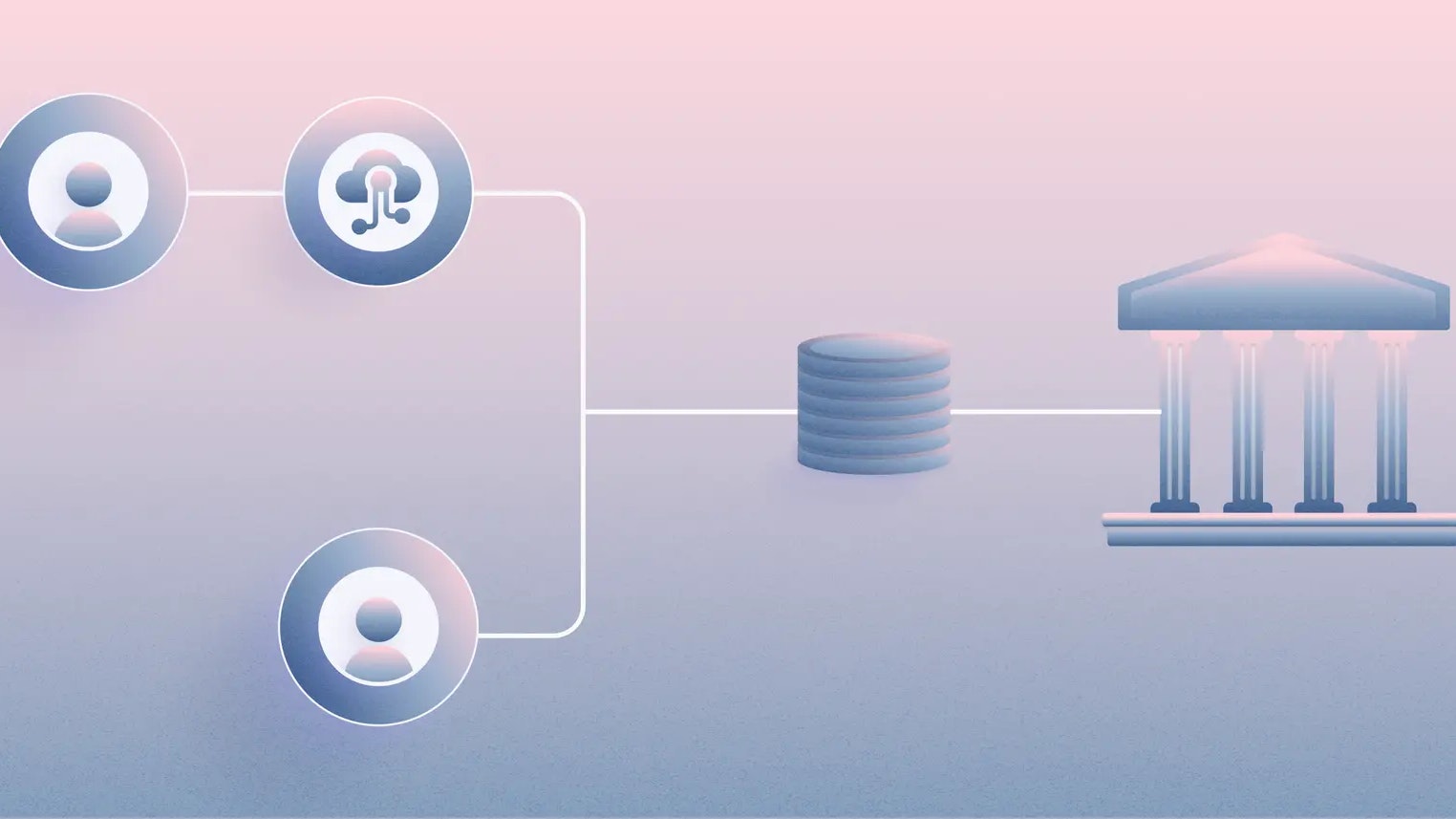

There are two primary kinds of FBO accounts in fintech. The first is a company-held FBO, where the fintech company holds an account for the benefit of its customers. In this model, the fintech is the account owner for legal purposes and manages funds on behalf of its customers, but the funds in the account may still be payable on demand to the end user.

The second major kind of FBO in fintech is a bank-held FBO, where it’s a fintech’s partner bank that holds an account for the benefit of a company’s customers. In this model, the bank is the legal owner of the account and manages funds on behalf of the fintech’s customers using instructions from the fintech on how to allocate and disburse the funds based on customer transactions.

In both cases, the FBO account is also called a “pooled” account, because it essentially pools together customer funds into a single account at the bank. It’s then the job of the fintech intermediary to maintain a detailed record — a ledger — of which funds in the pooled account belong to which customers. This requires meticulous transaction tracking and matching, including recording all deposits, withdrawals, transfers, and other transactions, as well as matching individual customer transactions with the aggregate transactions reflected on a pooled account to ensure that all account balances are accurate and up to date.

Understanding the fundamental differences between DDA and FBO accounts

DDAs and FBOs are fundamentally different types of accounts that may stand on their own or may need to work hand-in-hand. For example, an FBO model like one of the two primary fintech models mentioned above may have an underlying DDA — but the FBO layer ultimately changes the level of access that an end-user has to that account.)

Below, we break down some of the core areas where DDAs and FBOs are considerably different, and help shed light on what this means for an end-user in each of the cases:

Ownership and access to the account

As mentioned already, the first way in which DDAs and FBOs differ considerably from one another is the way in which an end-user can engage with the account. With a DDA, an end-user has a direct relationship with their bank, and — by extension — direct, on-demand access to their funds. Funds in a DDA are payable upon demand, providing startups with the flexibility to manage their cash flow efficiently. This is particularly important for operational activities such as payroll, vendor payments, and other day-to-day expenses.

With an FBO, the end-user has an indirect relationship with the bank, because there’s an intermediary that facilitates that relationship. So a fintech that serves as a functional player between a banking customer and a chartered partner bank, for example, might operate under the FBO model.

While both DDAs and FBOs allow startups to make decisions about withdrawals, deposits, and transfers without needing approval from a third party, the direct relationship facilitated by DDAs also allows startups to take actions like executing a DACA on the account or transferring ownership of the account in a contract or will.

Because of the distinctions in ownership, the DDA model is good when an end user wants what people would think of as a checking account. In an FBO model, what the end user gets isn't a bank account at all. The FBO model is usually used when a company wants to provide an online wallet (like, your Gemini fiat wallet, or your CashApp balance).

Deposit insurance

The other major area of differentiation between DDAs and FBOs is how the two types of accounts are insured. With a DDA, insurance is pretty straightforward — deposits are directly insured by the FDIC up to $250,000 per depositor, per insured bank. This is simple and can give users peace of mind that any funds up to that insurance maximum would be recovered in the case of a bank failure, for example.

Things are less clear cut with FBOs, in which funds may be insured if properly structured and disclosed, but the coverage can depend on how an account is managed and the specific customer disclosures. FBOs may only qualify for what is known as “pass-through” FDIC insurance, where the end-user (and owner of the funds) won’t be directly insured. Instead, the insurance would need to pass through the intermediary account owner before going on to the end-user. In order for this to work well, all parties involved need to structure the accounts in proper accordance with FDIC requirements. Then in the event of a bank failure, it’s up to the FDIC to decide whether the requirements for pass-through insurance have been fully met and, thus, whether funds will receive FDIC protection.

Security and compliance

There’s no hard rule about whether DDAs or FBOs are inherently safer, as the safety of each account will mainly come down to how the account is managed and the specific safety measures that are put in place by a bank or third-party intermediary.

In both cases, there is heavy regulation by banking authorities such as the Federal Reserve, the FDIC, and state banking agencies. These institutions enforce stringent regulations prevent fraud and maintain the stability of the financial system. This regulatory framework includes regular audits and examinations, ensuring that banks adhere to high standards of security and operational integrity.

Then there’s an additional layer of fintech-specific compliance requirements in the event that the banking relationship involves a partnership between a bank and fintech, which can be true for both DDA and FBO accounts, as explained above. So the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), for example, will expect fintechs to adhere to state-specific fintech laws. Some fintechs — particularly those that hold money-transmission licenses — are also held to high transparency standards, with requirements about disclosing how customer funds are managed.

As for security measures meant to further protect end-users — things like end-to-end encryption and multi-factor authentication (MFA) — it will be up to the individual banks or fintechs to implement stringent security measures to ensure the safety of their customers and end-users. (Account type aside, it’s generally true that security measures implemented by fintechs tend to be more sophisticated than big banks, which don’t always have the robust encryption, secure APIs, and stringent data protection regulations that fintechs do.)

How to determine whether your account is an FBO or DDA

Just as you might care to dig into the financial health of your bank to feel more confident about where you’re storing your company’s money, you might be curious to better understand the exact structure and setup of an account.

The most straightforward way to know how your own account is set up is to review your account agreement and terms of service. These documents should explicitly state the type of account you have. In some cases, information about your specific account setup might also be available on your regular account statements or in any of the account information you can pull up in your online banking dashboard.

If all else fails, you can always reach out to your bank or fintech’s customer support team to make sure that you understand how your account is set up and what the implications of your particular account setup is.