Points of view: What quality feels like to investor Clayton Bryan

A single idea can open in countless directions.

Points of view gathers perspectives around a concept, with each participant choosing their own journey through questions, answers, and the imagination and marvels in between.

For our first Points of view, we explore the concept of details — and how a few sharp minds have polished their ability to tune into them and the subtle signals that separate good work from great work. What follows is a glimpse into that fine-grained attention and how it moves the work forward.

Here, we spoke to Clayton Bryan, Partner at 500 Global, a venture capital firm investing in ambitious founders across geographies and sectors. Bryan shares his thoughts on the preparation that drives quality thinking, the process of testing the harmony within a founding team, and the signal that a masterful deflection actually sends.

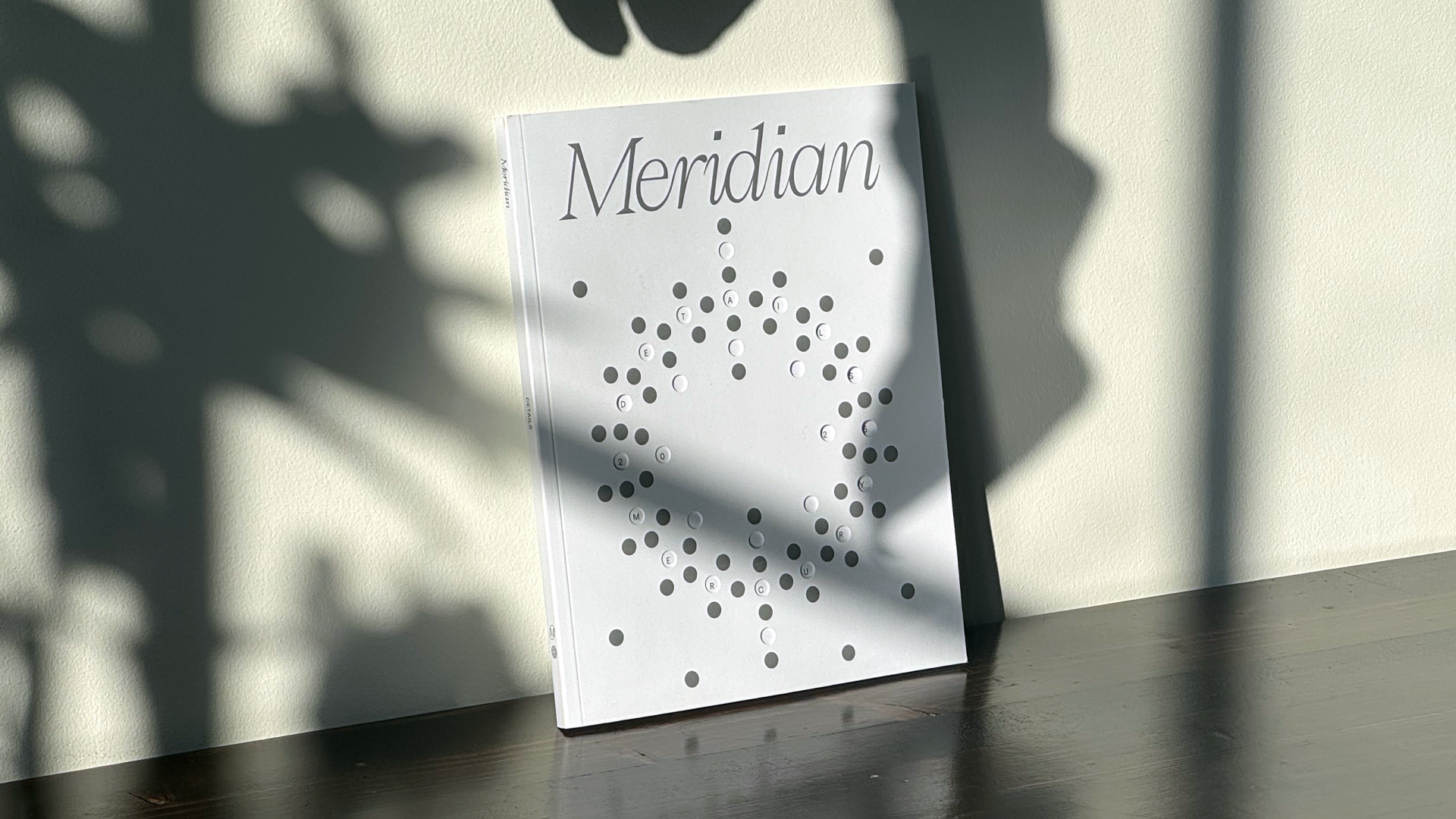

Read more stories like this one in Meridian: Details — on the subtle choices that shape how ambition comes to life.

What does quality feel like?

Quality has a certain resonance. It’s a feeling of deep preparedness that you sense almost immediately. I see it in founders who have not just studied their market, but the history of their market. They’ve spent time with the ghosts of startups past — they can tell you what was tried before, why it failed, and what fundamental truth has changed to make their attempt different. There’s no hand-waving; there’s just a quiet confidence built on rigorous homework.

Then, that resonance deepens when you hear how they talk about their customers. It moves beyond “customer obsession” as a buzzword and becomes a tangible empathy. The best founders I’ve worked with can practically channel their ideal customer. They’ve spent so many hours in conversation that they can articulate the customer’s anxieties, their workflows, and their secret hopes with stunning clarity. They’ve moved from personas on a slide to a psychological understanding of the person they’re building for.

They’ve spent time with the ghosts of startups past — they can tell you what was tried before, why it failed, and what fundamental truth has changed to make their attempt different.

Ultimately, quality feels like taste. It’s the craftsmanship in their thinking — the ability to hold all of this complexity and then articulate it with a simple, elegant clarity. It’s the moment a founder can take me on a journey from a broad historical context to the specific, nagging frustration of a single user, and make it all feel like one coherent, compelling story. That’s when you know you’re sitting across from a true, high-quality builder.

What’s a detail you notice that others tend to overlook?

I focus intensely on the harmony — or dissonance — in a founding team’s definition of success. On the surface, every founder gives the same answer: “We want to build a billion-dollar company.” But that’s just the table stakes response. The detail I’m looking for lies beneath that, in the subtext of their individual ambitions and personal stakes. My process for this involves meeting with co-founders as a group, and then carving out time to speak with each one individually.

In the group setting, you see the well-rehearsed choreography. In the one-on-ones, you hear the unfiltered dream. I’ll ask something like, “Imagine this is wildly successful five years from now. Paint me a picture of what that day looks like for you.”

What I’m listening for is alignment in the texture of their answers. Sometimes, you find a beautiful harmony. One founder might see this as their life’s work, the culmination of their entire career. Another might describe the same long-term vision, but focus on the joy of building the team that gets them there. The timelines and emotional endpoints are in sync.

But occasionally, you hear a subtle, dangerous dissonance. One founder is describing a 10-year crusade to redefine an industry, while the other is implicitly signaling a desire for a fast, life-changing exit in three years to move on to the next thing. Neither is wrong, but those two desires are like different engines trying to power the same car. That subtle misalignment, which can be easily overlooked in the early days of excitement, is often the hairline fracture that splinters the entire company when the real pressure sets in.

You can agree on every feature on the roadmap, but if you haven’t aligned on the destination and just how fast you need to get there, you’re bound to run out of road.

This isn’t just a theoretical exercise; it’s about uncovering the human reality of the venture. I had a situation last year that crystallized this for me, where my role shifted from investor to something more akin to a marriage counselor.

I was working with a two-founder team, both brilliant and deeply committed on the surface. But in our individual conversations, a critical divergence emerged. One founder confessed they were emptying their personal savings to make the company work. You could feel the palpable urgency in their voice; this venture wasn’t just a project, it was their life’s work. The other co-founder, who was in a more stable financial position and was self-financing, had a different clock. They were passionate, but described the company as a major focus for the “next 3-5 years, maybe a decade,” but explicitly stated it wasn’t their “end all, be all.”

There was no right or wrong answer, but there was a fundamental problem. One had a short runway and a deep, burning need to make this the thing, while the other had the privilege of a longer-term, more measured perspective. It wasn’t a conflict over product or strategy, but a misalignment in the very definition of success and sacrifice.

In the group setting, you see the well-rehearsed choreography. In the one-on-ones, you hear the unfiltered dream.

Initially, I hoped to find a middle ground, but it became clear my role wasn’t to patch up the partnership, but to help them see the truth and preside over an amicable divorce. It was one of the hardest but most important things I’ve done for a team.

And it was the right call. They went their separate ways, and remarkably, both raised successful funding rounds for their new, respective pursuits. They are both happier, and they even maintain a healthy working relationship — one’s company is now an important vendor for the other. That experience cemented it for me: You can agree on every feature on the roadmap, but if you haven’t aligned on the destination and just how fast you need to get there, you’re bound to run out of road. It’s a quiet detail, but it determines everything.

What’s the quietest thing that’s ever changed your mind?

In venture, you’re often looking for reasons to say ‘no,’ for the big, glaring red flags. But the thing that most often and most quietly changes my mind is the echo of an unanswered question. It’s not a loud, dramatic moment. It’s the subtle, intentional misdirection from a founder during diligence.

The best founders don’t have every answer, especially at the earliest stages.

It plays out like this: I’ll be digging into a key part of their strategy, maybe a question about customer acquisition costs or a potential moat. The question is specific and asked with genuine curiosity. But instead of a direct answer, I get a masterful deflection — a pivot to another, shinier part of the business or a beautifully polished, but ultimately empty response. It’s the conversational equivalent of a magician’s sleight of hand: “Look over here, not over there.”

This is quieter than a lie, but far more telling. The best founders don’t have every answer, especially at the earliest stages. I actually have immense respect for a founder who can say, “That’s the key question we’re still wrestling with, but here's how we're approaching it.” That honesty builds incredible trust.

But that quiet avoidance, that refusal to engage with a tough question head-on, is a powerful signal. It tells me that there may be a fundamental flaw they are unwilling to face, or worse, that their instinct under pressure is to obscure rather than clarify. It’s a quiet tell that predicts how they’ll handle much harder conversations down the road with their team, their board, and their customers. And in my experience, that signal is one of the most reliable predictors of future trouble.

Read more Points of view on details — with Nopalera founder Sandra Lilia Velasquez, Copytree editor in chief Paige Schwartz, and Esri UX designer John Nelson.

About the author

Managing Editor at Mercury.